|

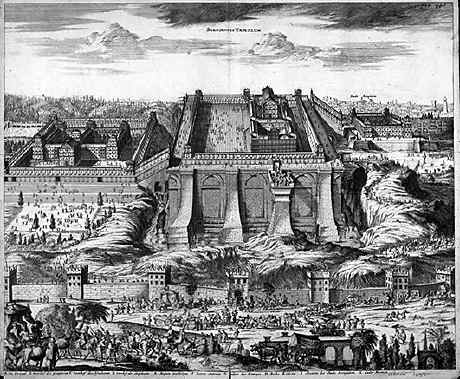

the temples at Jerusalem

CHAPTER XXXIX

part III - Freemasonry, Religion and Civilisation

THE SQUARE AND COMPASSES

W.

M. Don Falconer PM, PDGDC

King Solomon’s temple

was built to a Phoenician pattern belonging to a religious system then at least

2,000 years old. It was renowned for its lavish beauty and opulent furnishings.

The temple is a symbol of freemasonry.

References to the

construction of King Solomon's temple at Jerusalem have been included in the

rituals of the operative freemasons since ancient times. In operative lodges the

layout of the lodge room in each of the several degrees symbolises either a

stoneyard or the temple building at one of the various stages of construction.

As he participates in each of the several degrees, the candidate progressively

represents the various types of stone used in the building, until ultimately he

represents the plan of the temple. The ceremonial for each degree is based on

the preparation and usage of the relevant stone during construction and

ultimately on the application of the plan to achieve completion of the temple.

The way in which a stone is prepared by a stonemason in the stoneyard and

utilised by fitters and erectors on the building site, in conjunction with the

application of the plans and gauges, is used to illustrate how an individual

should prepare himself for the life hereafter. The moral lessons imparted are

also illustrated by the application of the various working tools used at the

various stages of the work, not only in the shaping, testing, fitting and

marking of the stones, but also during erection on the site. Many aspects of the

operative ceremonials and catechisms have been included in the rituals of

speculative freemasonry, though in a very abbreviated form.

One of the most learned

and distinguished of the early English Freemasons was the Rev Dr George Oliver

DD, who studied and wrote extensively on ecclesiastical antiquities and all

aspects of speculative Freemasonry. He was descended from an ancient Scottish

family of that name, some of who moved to England in the time of King James I.

In 1801 he was initiated in St Peter's Lodge in the city of Peterborough, by his

father the Rev Samuel Oliver. In his renowned work, the Revelations of the

Square, Dr Oliver says:

"The Society adopted the

Temple of Solomon for its symbol, because it was the most stable and the most

magnificent structure that ever existed, whether we consider its foundation or

superstructure; so that of all the societies men have invented, no one was ever

more firmly united, or better planned, than the Masons . . . The edifices which

Freemasons build are nothing more than virtues or vices to be erected or

destroyed; and in this case heaven only occupies their minds, which soar above

the corrupted world. The Temple of Solomon denotes reason and intelligence."

This must be one of the

most succinct yet comprehensive explanations ever given in respect of the

foundation, purpose and symbolism of Freemasonry. It also typifies all aspects

of the operative craft from which speculative Freemasonry is derived.

Since

the earliest times, man has built temples or shrines where he could worship his

own god in his “house”. The Tower of Babel is the first such

structure mentioned in the Bible, Babel being the name of one of the chief

cities founded by Nimrod in the land of Sumer, or ancient Babylon. Nimrod was a

prodigious builder and was King of Babylon at the time of the Tower of Babel.

Although as yet there is no archaeological evidence to confirm the existence of

a city and tower of Babylon before about 1800 BCE, a text of Sharkalisharri, who

was King of Agade in about 2250 BCE, mentions his restoration of the

temple-tower or ziggurat at Babylon, which implies the existence

of an earlier sacred city on the site. It is now believed that when Ur-Nammur,

the King of Ur, built a ziggurat in about 2100 BCE, it replaced

the first Tower of Babel that probably was constructed prior to 4000 BCE. The

ziggurat was a series of superimposed platforms ranging from about 10

to 20 metres in height, which progressively diminished in area and were accessed

by ramps or stairways. The structure was surmounted by a temple, to which it was

believed that God would descend and communicate with mankind. The traditional

history of the Masons' Guilds stated that their trade secrets were first given

to the trade by Nimrod. The ritual of the operative Free Masons still includes

the old “Charges of Nimrod”, in which the first charge requires

that all Free Masons shall be true to their God, their King, their Lord and

their Masters.

Abram,

who was born in Ur of the Chaldees in about 2160 BCE, received a Divine call

when he was 70 years old and told to search for a land where he could build an

Israelitish nation free from idolatry. To fulfil his mission, Abram began his

journed by moving to Harran on the Balikh River, a tributary of the Euphrates

1,000 kilometres northwest of Ur, where he stayed until his father died about

five years later. Thence he travelled southwards in stages to the vale of Moreh,

between Mount Ebal and Mount Gerizim in Canaan, where Yahweh

promised Abram that he would possess the whole of the land southwest from the

Euphrates River. Abram “built an altar to the Lord, who appeared unto him”

to express his thanks for the Lord’s promise. As the Canaanites were jealous of

Abram, he soon moved south to the mountainous district between Beth-el and Ai,

where he also built an altar to Jehovah. Abram continued to move southwards

until driven by famine from the Negeb into Egypt, but he later returned to the

mountainous district as a wealthy man and again established the worship of

Jehovah. God reiterated his promise to Abram, who then moved to Mamre near

Hebron, where he built another altar.

In about 2080 BC, after Abram had rescued his

nephew Lot by defeating a confederation of four Babylonian kings under the

leadership of Chedorlaomer the despotic King of Elam, Melchizedeck the King of

Salem, referred to in the Bible as the “priest of the most high God”,

blessed Abram in the name of God. Melchizedeck is said to have prefigured Christ

by offering bread and wine as memorials of sacrifice. Because Abram saw in this

sacrament a messianic revelation of the “most high God” El

Elyon, Abram paid tithes to Melchizedek in token of this recognition.

God then renewed his promise to Abram, but said that his people would spend 400

years in a foreign land before they should inherit Canaan. God also revealed

himself to Abram as the “all powerful God” El Shaddai,

who could consummate his promise of a coming Redeemer. At this

juncture Abram, which signifies “eminent father”, changed his name

to Abraham signifying “father of a multitude”, as a token in

recognition of what El Shaddai would do in his redemptive power.

This renewal of the covenant was sealed by the introduction of the ceremony of

circumcision, as a spiritual symbol of the purification of life at its very

source and also signifying the messianic hope for a Redeemer and

Covenant-Fulfiller. Abraham was 175 years old when he died, 115

years before Jacob and his family migrated to Egypt. As Jacob passed out of

Canaan in about 1870 BCE, God gave him an assurance that his descendants would

return to the Promised Land.

As the patriarchs

Abraham, Isaac and Jacob were semi-nomadic, they could not build a permanent

shrine for worship, as was the custom in the cities of Mesopotamia when Abraham

left Ur. After a sojourn of 430 years in Egypt, the Israelitish nation came into

being with the institution of the Feast of the Passover and the beginning of the

Exodus under the leadership of Moses in about 1440 BCE, guided by the

Pillar of Cloud by day and the Pillar of Fire by night.

During the second year of the Exodus, Moses made the most zealous intercessions

on behalf of his people, spending two periods of forty days and nights on Mount

Sinai. Moses was rewarded when the glory of the Lord was revealed to him, the

tables of the law were renewed and a new covenant was made with Israel. In

recognition of the new covenant and in accordance with directions Jehovah

gave to Moses, a Tabernacle or “tent of congregation” was erected

as a portable sanctuary. The Tabernacle was 30 cubits long and 10 cubits wide

oriented from east to west. It was placed within and near the western end of a

court 100 cubits long and 50 cubits wide, enclosed by a fence of shittim or

acacia wood pillars 5 cubits high and braced by stay ropes. The structure

supported “fine twined linen” sheets hung from rods. A

“brazen altar”, or “altar of burnt offering” was placed

just inside the court, near the entrance gate at the eastern end. A bronze

“laver”, in which the officiating priests washed, was placed midway

between the brazen altar and the entrance to the Tabernacle at its eastern end.

The Tabernacle was composed of two parts, the “mishkan” or

tabernacle proper and the “ohel”, or tent.

In its

strictest sense “tabernacle” refers to the ten linen curtains that

were hung inside the tabernacle proper, along the narrower western wall and the

longer northern and southern walls. These walls consisted of planks of shittim

or acacia wood plated on both sides with sheets of gold. The curtains had

figures of cherubim woven into the blue, purple and scarlet tapestry work. The

interior of the mishkan was divided into two compartments by a veil of similar

material, colour and design as the curtains. The larger of these compartments,

20 cubits long and 10 cubits wide, was at the eastern end and called the “hekhal”,

which is the “Holy Place”. The western compartment was a perfect

cube of 10 cubits called the “debir”, which is the “Holy of

Holies” where the Ark of the Covenant rested under the

protective wings of two huge cherubim. The whole was covered by the “ohel”,

a fly roof of foxy black or brownish canvas made of goats'-hair called camelot,

which is still used by nomadic Arabs. The Tabernacle was used as the provisional

meeting place between God and the “chosen people” until long after

their entry into Canaan. Under the Judges it was at Shiloh and in Saul's reign

it was at Nob and later at Gibeon. Although David erected another Tabernacle at

Jerusalem for the reception of the Ark of the Covenant, the

original Tabernacle of Israel remained at Gibeon until the days of King Solomon,

together with the brazen altar used for sacrificial offerings.

The

Hebrews naturally attached a great deal of symbolism to various aspects of the

Tabernacle and also to the related ceremonials. The “tent of congregation”

typified God dwelling with his people and the Ark of the Covenant

was a constant reminder of God's presence and forgiving love. The twelve cakes

of shewbread, placed on a table midway along the north wall in the Holy

Place, signified the dedication of the Twelve Tribes of Israel to divine

service. The menorah, a seven branched candlestick of pure gold

that was 3 cubits or more high, was placed midway along the south wall to

represent Israel as a people called to be the “children of light”.

The incense ascending from the golden altar of incense that was placed in the

middle of the space on the eastern side of the inner veil, near to and in front

of it, symbolised the act of prayer. The early Christian evangelists interpreted

the two compartments of the Tabernacle as being characteristic of the earthly

and heavenly aspects of Christ's ministry, saying that by the symbolism of the

rent veil Christ had opened up for everyone a way into the Holy of Holies.

The layout and furnishings of the Tabernacle and its surrounding court were

replicated in lavish detail and supplemented in the temple constructed by King

Solomon at Jerusalem.

Because of the important role Egypt played in the

history of the Hebrew people, as well as the strong intellectual and cultural

influence of the pharaonic civilisation throughout the Mediterranean region and

the close links then existing between the two peoples, it was believed until

recently that Egypt had provided the model for King Solomon's temple in

Jerusalem, even though it did not resemble any temple in Egypt. Archaeological

excavations in northern Syria in the 1930s were the first to throw doubt on the

belief of its Egyptian heritage. Excavations at Hazor in northern Palestine,

during the 1950s, reinforced these doubts. However it was the salvage

excavations carried out from 1970 to 1976 in a bend of the Euphrates River, on

the site of what is now Lake el-Assad, which confirmed beyond doubt that King

Solomon’s temple was built to a Phoenician pattern conforming to the traditions

of a religious system that had been followed for 2,000 years or more. At least

3,200 years ago, about the time when Moses was on Mount Sinai, the Phoenicians

became the greatest developers and builders around the Mediterranean. Their

pre-eminence in building continued until the conquest of the region by Alexander

the Great in 333 BC. The Phoenicians were more advanced culturally than the

Hebrews and they played a significant role in the design and construction of

King Solomon's temple, their long experience in temple building undoubtedly

having a significant influence.

The

religious traditions that developed in the countries in the “fertile

crescent” of the Near East and in the Levant were bringing about

significant changes in human attitudes to the divinity as long ago as 5,000

years. These attitudes were reflected in the designs of temples that became the

pattern for those constructed by the Phoenicians. The temples were elongated

about 3:1 in plan, had a single entrance at the narrower eastern end and were

subdivided into compartments that provided a progressive transition from the

profane outside world to the inner and most holy sanctuary. The deep

significance of this progression of priests and worshippers, commencing from the

profane outside world and leading to the sacred precincts, is reflected in the

names of the compartments in the Tabernacle and later in King Solomon's temple.

This arrangement was typified in the temple of King Solomon at Jerusaslem, which

had a porch or anteroom, the ulam, at the eastern end flanked by

two great pillars called Jachin and Boaz. The porch opened into the main hall of

worship, the Holy Place or hekal, which had a table

of offering and other furnishings and was the place for divine service and the

performance of ritual. At the western end was the Holy of Holies

or debir, called the place “where God dwelt” and

where the “Ark of the Covenant” was kept, which was accessible

only to the priesthood on specific occasions.

The

many temples that have been excavated are not identical in design, but they are

sufficiently alike to prove beyond doubt that they had a common religious theme.

The oldest known temples or sanctuaries of this type were three found at Tell

Shouera on the eastern branch of the headwaters of the Euphrates River in the

foothills of northern Syria. In comparison with King Solomon’s temple, they

range from about the size of its Holy of Holies to a little larger

than its overall size including the storage chambers surrounding it on the

northern, western and southern sides. They are about 4,500 years old and were

built sequentially over several generations. A Canaanite temple of the same

general description and about 4,000 years old was discovered during the 1950s

while excavating the ancient lower city of Hazor in northern Palestine. Hazor

was only occupied for about 500 years, when it was destroyed and burnt, but

never reoccupied. Another temple excavated at Ebla, 300 kilometres to the

southwest of Tell Chouera and built about 3,800 years ago, is almost identical

in size to King Solomon’s temple, although the Holy of Holies is

significantly shorter. In King Solomon’s temple the Holy of Holies

was on a podium, but at Ebla it was augmented by a substantial niche in the

western wall, which allowed a small room to be placed between its porch and the

main hall of worship which is about the same size as it was in King Solomon’s

temple.

The

greatest volume of evidence comes from the salvage excavations on the site of

Lake el-Assad during the 1970s, where seven temples were unearthed all built

several hundred years before the first temple at Jerusalem. Of these temples,

four at Emar range from about half to two-thirds the size of King Solomon’s

temple and are from 3,400 to 3,200 years old, corresponding with the brief

period during which a Hittite city existed there. The two larger temples at Emar

were built parallel and close together to form a double sanctuary. A road

between them gave access to a common terrace for sacrificial offering that was

located behind them, instead of in front as at Jerusalem. A similar temple

excavated at Moumbaqat, midway between Emar and Ebla and intermediate in age, is

even larger than the largest at Tell Chouera. The first Syrian temple

discovered, which is that at Tell Ta'Yinat, is almost identical in size to King

Solomon’s temple and probably was constructed a little later. Some of the Syrian

excavations also show evidence of stub walls near the western ends of the

temples, which are thought to have been the locations of internal timber walls,

similar to the one that screened the Holy of Holies in King

Solomon’s temple. The foregoing archaeological evidence clearly shows that King

Solomon’s temple and also its precursor, the Tabernacle of Israel, were both of

the form originally established by the Canaanites and subsequently developed by

the Phoenicians.

When Saul died in about 1010 BCE, David became the

King of Judah and seven or eight years later he was anointed King over all

Israel. After David had consolidated his power and built a permanent residence

for himself, the lack of a shrine of Yahweh seemed invidious to him. He said:

“I dwell in a house of cedar, but the Ark of God dwelleth within curtains”.

Because his hands were stained with the blood of his enemies, David was

precluded from building a temple to the Lord, but he collected materials,

gathered treasure and purchased a site for the construction. The site chosen was

the threshing-floor of Araunah the Jebusite, within the area now called Haram

esh-Sherif on Mount Moriah on the east side of the “Old City” of

Jerusalem. Whilst the precise location of the first temple is not known it is

believed that the highest part of the rock, now covered by the mosque known as

the “Dome of the Rock”, almost certainly was the position of the

Holy of Holies. Jewish tradition relates that a secret vault was

constructed beneath the temple, in which confidential meetings could be held and

all sacred treasures and documents could be stored. Such a vault also features

in masonic tradition and is a key element in several of its ceremonies. The

construction of such a vault under ecclesiastical and other buildings of

importance was common in ancient times and virtually became an essential element

in medieval times. Recent seismological surveys indicate that there probably is

a cavern beneath the mosque, but excavations to confirm the existence of the

traditional vault are precluded at present.

King

Solomon commenced construction of the temple in the fourth year of his reign and

completed it seven years later, in about 950 BCE. To facilitate the work he

entered into a treaty with Hiram, King of Tyre, whereby Hiram would permit

Solomon to obtain cedar and cypress wood and blocks of stone from Lebanon.

Furthermore, Solomon's workmen would be permitted to fell the timber and to

quarry and hew the stones under the direction of Hiram's skilled workmen. In

addition, Solomon was provided with the services of a skilful Tyrian artisan

named Huram, to take charge of the castings and of the fabrication of the more

valuable furniture and furnishings of the temple. In return for all of the

services to be provided by Hiram, Solomon agreed to send to him every year

4,400,000 litres of crushed wheat and 4,400,000 litres of barley, as well as

440,000 litres of wine and 440,000 litres of oil. Solomon raised a levy of

forced labour out of all Israel, totalling 30,000 men, which he sent to Lebanon

in relays of 10,000 a month. Adoniram, who had been an officer of King David in

charge of labour gangs, continued under King Solomon and was placed in charge of

the levy working in Lebanon. King Solomon also employed 70,000 burden bearers

and 80,000 hewers of stone in the hill country, as well as 3,300 officers in

charge of the men carrying out the work. Some thirty years after the completion

of the temple, when Rehoboam sent Adoniram to enforce the collection of taxes,

the exasperated populace rebelled and stoned Adoniram to death.

King

Solomon’s temple was a prefabricated building oriented due east to west. It was

constructed of accurately shaped blocks of limestone that were quarried and

dressed in or near Jerusalem and assembled without mortar. The temple had a

single entrance at the eastern end, accessed through an uncovered porch. The

porch or ulam was 10 cubits in length along the axis of the temple

and 20 cubits wide. Looking towards the east from inside, the porch was fronted

by two great pillars or columns. The pillar on the right or south side was

called “Jachin” and the pillar on the left or north side was

called “Boaz”. All of the timber used in the temple came from the

forests of Lebanon. The temple had olive wood doors and was lined with cedar

wood, ornately carved and inlaid with gold. The compartments of the Tabernacle

were replicated in King Solomon's temple, but they were twice as large. The

porch gave entrance into the Holy Place or hekhal,

which was 40 cubits long, 20 cubits wide and 30 cubits high, lit by latticed

windows near the ceiling. This hall was accessible only to priests and was used

for daily worship, for religious ritual and for the presentation of offerings.

The Holy of Holies or debir was at western end of

the building. It was a perfect cube of 20 cubits and set on a podium to maintain

the same ceiling line as that in the Holy Place. There were no

windows in the Holy of Holies, which received its light only

through the doorway from the Holy Place when the curtains were

open. The Holy of Holies was accessible only to the high priest,

probably only once a year for the atonement ceremony.

The

temple was surrounded on the north, west and south by store chambers three

stories high. Among these, on the southern side, was the “Middle Chamber”

to which access was gained by a winding stair in the southeast corner of the

building. The whole structure was on a platform about 2 metres higher than the

upper or inner court that surrounded it, which was reached by ascending ten

steps. This inner court was raised above the surrounding great or outer court,

which was reached by ascending eight steps. The outer court was raised above the

surroundings and was reached by ascending seven steps Each of these courts was

enclosed by walls comprising three rows of hewn stone, surmounted by a row of

cedar beams. In the upper or inner court, as in the court of the Tabernacle,

there was a brazen altar of burnt offering, a brazen sea and ten brazen lavers

for use by the priests in their ablutions and for ceremonial purification.

Although smaller than any Egyptian temple, King Solomon’s temple was a

magnificent edifice that surpassed any preceding temples. King Solomon’s temple

was noted for the lavish beauty of its detail and opulence of its furnishings,

rather than for its size. No stonework was visible inside, because the

compartments were ceiled and panelled with cedar wood and the floors were

planked with cypress. The Holy Place was accessed at the eastern

end through double folding doors of cypress wood, each divided into upper and

lower sections. At the western end of the Holy Place double doors

of olive wood gave access to the Holy of Holies. Both sets of

doors were usually left open, but they were screened with veils ornamented like

those in the Tabernacle. The walls and doors were carved with palm trees,

garlands, opening flowers and cherubim, all richly inlaid with gold. The ceiling

and floor of the Holy Place and the whole of the interior of the

Holy of Holies were overlaid with gold plate.

The

furnishings of the Holy Place included an altar of incense and

twelve tables for the loaves of shewbread, as well as ten “menorah”

or golden seven-branched lampstands, often called lampsticks. Inside the

Holy of Holies two cherubim that stood 10 cubits high, were carved from

olive wood and overlaid with gold to symbolise the majestic presence of God.

Research has revealed that the cherubim would have been winged sphinxes, each

with the body of a lion and a human head. This hybrid was extremely common in

the iconography of western Asia between 1800 BCE and 600 BCE. The cherubim stood

in a brooding attitude with outstretched wings, so that the tips of their

adjacent wings touched above the Ark of the Covenant in the middle

of the apartment and the tips of the two outer wings touched the north and south

walls. The Ark of the Covenant was made of shittim or acacia wood,

overlaid with pure gold inside and outside. It contained the two tables of stone

on which the Ten Commandments were engraved, defining the terms of

God's covenant with Israel.

The two great pillars at the porch or entrance to

King Solomon's temple were hollow and cast of bronze 12 cubits in circumference

and four fingers thick, standing 18 cubits high. Double capitals surmounted the

pillars and were 5 cubits in their combined height, probably having been cast in

two separate parts. The chapiter or lower part was of lotus work and comprised

four open and everted petals each 4 cubits wide. The capital or upper part was a

bowl, not a sphere as is often said. The Tyrrians cast the hollow columns in

moulds dug in the ground, using what is called the “lost wax”

method that was developed by the Assyrians in the Bronze Age, probably in about

1200 BCE. In this method the mould is formed around a wax core that melts away

during casting. With large castings like the pillars, the core is formed with

sand or earth and coated with thick wax. The columns of King Solomon’s temple

were common in Syria, Phoenicia and Cyprus at the time and the Tyrrians were

experienced in this method of casting.

Modern

research indicates that the upper bowl probably was a vessel to contain oil,

which could be lit at night. It is known that similar decorated pillars were

used at shrines in Palestine and Cyprus during the period 1000 BCE to 900 BCE,

when King Solomon’s temple was built. The Greek historian Herodotus, writing in

about 450 BCE, described two large pillars that stood near the temple of

Hercules at Tyre, which “shone at night”. Like the Phoenician

models, the two immense incense stands at the porch of King Solomon's temple

would have illuminated the facade of the temple on Mount Moriah at night, whilst

also catching the first glint of the sunrise at Jerusalem. They have been

interpreted as sacred obelisks, their blazing smoking wicks recalling to

worshippers the pillars of fire and cloud that led the Israelites of old through

the wilderness.

The

pillars were completed and named before the temple was dedicated. Although it

has often been said that the names of the pillars were to enshrine the memory of

David's ancestry, it is now known that this was not their purpose and

interpretation. It has been shown convincingly that the names of the two great

pillars inscribed on the columns stood for the initial, or key words, spoken by

oracles. In seeking to endow the Davidic dynasty with power and also to express

King Solomon's gratitude to the Almighty for his support, the oracles would have

used invocations such as: “Yahweh will establish (jachin) thy throne

forever” and “The king's strength (boaz) is in Yahweh”.

Contrary to views sometimes expressed, the bowls were not representations of the

then known terrestrial and celestial globes, nor did the pillars serve as

archives for the constitutional rolls.

Ancient temples usually served as state treasuries,

which were filled with the booty of conquests or emptied to pay tribute to

overlords, as the power of the land waxed and waned. King Solomon's temple was

no exception. Shishak, the Libyan prince who founded Egypt’s XXIInd Dynasty as

the Pharaoh Sheshonq I and reigned from 945-924 BCE, raided the temple when King

Solomon’s son Rehoboam was in power, taking all the treasure King Solomon had

accumulated. Later kings, including even Hezekiah who adorned the temple, used

the treasures to purchase the favour of allies or to pay tribute and buy off

invaders. Then followed idolatrous kings who desecrated the temple and allowed

it to fall into decay. By the time of Josiah, three centuries after it was

built, the temple was in need of considerable repair, which had to be financed

by contributions from the worshippers. Finally Nebuchadnezzar sacked and looted

the temple in 587 BCE, when he destred Jerusalem. The deportation of the Hebrews

into Babylonish captivity began in 722 BCE, when the Assyrian King

Tiglath-pileser captured Damascus, abolished the monarchy and detached the

northern and eastern regions of Israel, which he made into Assyrian provinces.

It continued when Tiglath-pileser imprisoned the last king of Israel, Hoshea, in

721 BCE after a three-year siege of his capital Samaria. Assyrian records say

that 27,290 people were then taken captive. The captivity continued

spasmodically until completed by Nebuchadnezzar a few years after he had

destroyed Jerusalem. Ezekiel, who was captured in 597 BCE and deported to

Babylon with Jehoiachin, became an important Hebrew prophet during the Exile.

Ezekiel's special mission was to comfort the captives in Babylon, which

comprised “all the house of Israel’. His prophesies were numerous,

including many concerning the surrounding nations, all of which were fulfilled.

He made many prophesies of Israel's final restoration, including his messianic

prophesy concerning the coming of Christ, when he said that the false shepherds

would give way to the True Shepherd. He also spoke of the

restoration of the land and of the people and gave his vision of the restored

nation and their worship in the new kingdom. The exiles were heartened in their

grief by Ezekiel's vision of a new temple, which he said would be erected during

their restoration. Ezekiel's description related to a temple that was similar to

King Solomon's temple, but he gave additional and specific information that

helps to establish details that are missing from the Biblical description of the

first temple. However Ezekiel's temple was never built, even when Zerubbabel

constructed the second temple at Jerusalem after the release from captivity.

Cyrus

came to the throne of Anshan, an Elamite region, in about 559 BCE and clashed

with a Median king. Cyrus captured the walled city of Ecbatana (the modern

Hamadan) when the Median army rebelled, as a result of which the Persians were

then in the ascendancy. Cyrus rapidly extended his conquests, defeating Croesus

the king of Lydia about 546 BCE and conquering Babylon in 539 BCE. Thus Cyrus

established the vast Persian Empire, which held dominion over Judea as a

province for the next two centuries. Cyrus established his capital at Pasargadae

in the land of Parsa, from where he ruled until his death in 530 BCE. In 538 BCE

Cyrus issued the following decree, releasing the Jews who were in exile in

Babylon:

“Thus saith Cyrus King

of Persia, all the kingdoms of the earth hath Jehovah, the God of heaven, given

me; and he hath charged me to build him a house in Jerusalem, which is in Judah.

Whosoever there is among you of all his people, his God be with him and let him

go to Jerusalem . . . and build the house of Jehovah . . .”

In

total about 42,360 Israelites returned progressively to Jerusalem, under the

leadership of Sheshbazzar or Zerubbabel in 535 BCE, under Ezra in 458 BCE and

under Nehemiah in 445 BCE.

The first small band

that returned to Jerusalem soon began rebuilding the temple, under Jeshua as the

high priest and Zerubbabel as the governor. Their meagre resources and the many

difficulties they encountered delayed completion of the temple until 515 BCE,

almost twenty years after the first group left Babylon, but long before all the

exiles had returned from captivity. Indeed, the temple was only completed then

because of the efforts of the prophets Haggai and Zechariah, who urged the work

on in the later stages. No accurate description of the second temple exists, but

the layout appears to have been similar to that of the first temple with the

height increased to 60 cubits. However it was much less ornate than King

Solomon’s temple, lacking the sumptuous finishes and only scantily furnished. A

lack of resources probably was the reason why the second temple was not built to

Ezekial's grand plan. So far as is known the second temple, like the tabernacle

of Israel, had only a curtain at the entrance to the Holy Place,

one menorah, one table of shewbread and a golden altar of incense.

Another curtain screened the entrance to the Holy of Holies, which

was empty. When Nebuchadnezzar sacked Jerusalem in 587 BCE the Ark of the

Covenant was destroyed. Nevertheless the second temple, usually referred

to as Zerubbabel's temple, survived for almost 500 years, which was much longer

than any other temple at Jerusalem. The Roman general Pompey took the temple

when he captured Jerusalem in 63 BCE, but did not harm it. However the Roman

consul Crassus plundered the temple of all its gold and other valuables nine

years later. The second temple was the focus point of the lavish reconstruction

and expansion carried out in later years by King Herod.

A

discussion of the temples at Jerusalem would not be complete without mentioning

King Herod's temple. Our principal source of information is Josephus, the Jewish

historian and priest who flourished in about 70 AD. Herod the tetrarch of

Galilee, known as Herod the Great, came from the Negeb between the Dead Sea and

the Mediterranean Sea. He was of Idumaean blood and Edomite stock, descended

from Esau. King Herod was an indefatigable builder, who wished to show his own

grandeur by restoring the temple as a larger, more complex and much more

beautiful building. He took great pains to carry out the reconstruction

piecemeal, without interrupting the ritual observances, even to the extent of

training 1,000 priests as masons to build the shrine. The work began in about

20 BCE and the main structure was finished in ten years, but the whole complex

was not completed until 64 AD. The temple area was twice the size of

Zerubbabel's temple and the total area of development more than ten hectares.

King Herod’s temple was burned when Jerusalem fell to the Roman armies in 70 AD.

The golden candalabrum, the golden table of shewbread and other valuables were

carried off to Rome. The bas reliefs carved on the triumphal arch of Titus in

Rome depict Roman soldiers carrying off the looted temple furniture.

It is

worth noting that the orientation of the temples at Jerusalem was the reverse of

the present orientation of Christian churches. A worshipper in the Holy

Place of the temple looked west to the Holy of Holies or

east through the entrance to see the rising sun. Christian churches usually have

their main entrance in the west and the altar in the east. Lodges of operative

Free Masons have always adopted the orientation of the temples at Jerusalem,

with the entrance in the east and the master in the west. The orientation of

lodges of speculative Freemasons is the reverse, probably because the compiler

and editor of the original “Constitutions of the Freemasons”

published by order of the Grand Lodge of England in 1723, the Rev Dr James

Anderson DD, was an influential Presbyterian clergymen who as a matter of course

would have adopted the orientation then in use in Christian churches. Another

possible reason is that early speculative ritualists may have been influenced by

an essential doctrine of that particular school of the Cabala that says:

“His Majesty . . . sits on a throne in the east, as the actual representative of

God”. Whatever its origin, the reversal of the orientation in lodges of

speculative Freemasons has caused confusion in the interpretation of their

symbolism, because the words of the ritual were adapted from Operative usage

based on the orientation of the temple. In conclusion it is worth quoting Dr

Oliver, to whom we have already referred, who said in his lectures on

Signs and Symbols: “The principal entrance to the lodge room ought

to face the east, because the east is a place of light both physical and moral;

and therefore the brethren have access to the lodge by that entrance, as a

symbol of mental illumination.”

back to top |

![]()