|

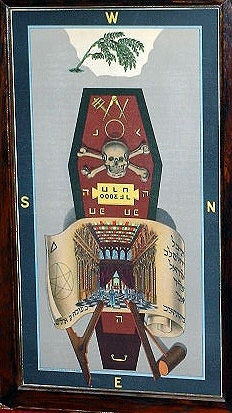

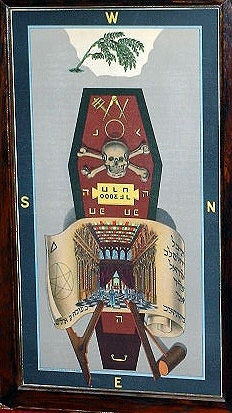

the tracing Board of a master mason

CHAPTER XXXIII

part II - Symbolism and the Teachings of Freemasonry

THE SQUARE AND COMPASSES

W.

M. Don Falconer PM, PDGDC

The dust shall return to the

earth as it was and the spirit shall return unto God who gave

it.

---Ecclesiastes 12:7

In 1811 Brother

Josiah Bowring, a well known portrait painter of London who had been

initiated in the Chichester Lodge in 1795, prepared a set of tracing

boards for his lodge. His tracing board of a Master Mason included a

large scroll draped over most of the lower half of the coffin. In

the centre of the scroll was an interior view of King Solomon's

temple, looking towards the Holy of Holies in the west, which

occupied nearly all of the area resting on top of the coffin. A

eulogy, comprising five lines of Hebrew characters, was inscribed on

the portion of the scroll overhanging on the right side of the

coffin. Various symbols were depicted on the portion of the scroll

overhanging on the left side. An epitaph, also in Hebrew characters,

was inscribed at the bottom of the scroll, part of it on the right

side of the overhanging portions and part of it on the left. Brother

Bowring's tracing boards are among the earliest known in the modern

format. They are of special significance, because Hebrew characters

were used for all inscriptions on the tracing board of a Master

Mason. Some 20 years after Brother Bowring had prepared his boards

Brother John Harris, an architectural draughtsman and

miniature-painter, also prepared a set of tracing boards that he

published in about 1821. His designs were similar to Brother

Bowring’s, except that Brother Harris omitted the scroll that is a

central feature of the tracing board of a Master Mason prepared by

Brother Bowring. Brother Harris also converted the Hebrew characters

on the coffin to equivalent cryptic characters or Roman numerals.

Most of the tracing boards used in modern speculative lodges have

been derived directly or indirectly from the set prepared by Brother

Harris.

As the general

appearance of Brother Harris's set of three tracing boards appealed

to the Emulation Lodge of Improvement, it decided to adopt them.

Even so, in about 1846, the Emulation Lodge of Improvement

commissioned Brother Harris to modify his design of the Master

Mason’s tracing board, to include a scroll inscribed in Hebrew

similar to that adopted by Brother Bowring in his design. Brother

Harris completed his new design about three years later. He included

Hebrew inscriptions on the scroll and also three Hebrew characters,

He, arranged on the coffin in the form of a triangle.

However, he did not use Hebrew characters for the other inscriptions

on the coffin, but continued to use the cryptic characters and Roman

numerals as on his earlier board. This tracing board is called the

"Improved Harris". In lodges that do not follow the

Emulation working, the scroll on the tracing board of a Master Mason

is usually omitted and the three Hebrew characters,

He, are represented by the Roman numerals

5. The “Improved Harris”, or Emulation

tracing board, provides the background that is essential for a

proper understanding of the tracing boards of a Master Mason. It is

an advantage to know the derivation and meaning of the words that

the Hebrew characters represent. It also is important to remember

that Hebrew is written from right to left, as also are the cryptic

characters used to replace Hebrew characters. All of the words

represented by the Hebrew characters and the substituted cryptic

characters are explained in the Geneva Bible published

by Thomas Bodley from 1560 onwards and also in the later editions

published by Christopher Barker from 1580 onwards, which is usually

called the Barker Bible.

The Geneva

Bible has comprehensive marginal notes. William Shakespeare

(1564-1616) and many eminent scholars and philosophers of that era

used it extensively. The Barker Bible includes those

marginal notes and also tabulations of Hebrew names and associated

words, with explanations of their meanings. Both Bibles continued in

popular use by educated people long after the Authorised

Version of King James was issued in 1611 and it would have

been very familiar to the early speculative ritualists. Most

Biblical names and other significant words in masonic usage were

derived from the unpointed Hebrew texts from which the Geneva

Bible and Barker Bible had been translated. As

those texts were written using only the twenty-two consonants

without vowels, their interpretation was often a matter of opinion.

Moreover, unless Hebrew characters are written with great care, some

can easily be mistaken for others, with consequential changes in

pronunciation and meaning. For example if the left leg of

He (the equivalent of H in English and

meaning a Window) inadvertently joins the top of the

character, it becomes Heth (the equivalent of a

guttural Ch in English and meaning a

Fence). If Tau (the equivalent of

T in English and meaning a Cross) is

written carelessly, it could easily be mistaken for either

He or Heth. As in the English language,

many Hebrew words also have various different meanings according to

the context in which they are used. Factors such as these would have

contributed to many of the variations found in the pronunciation and

interpretation of Hebrew words that are of significance in

freemasonry.

A

detailed examination of the Emulation tracing board of a Master

Mason will develop our understanding of the tracing boards in common

use and will put them in a better perspective. Most of what follows

is not included in lectures on the tracing board, nor is any

explanation of the symbols on the board and their meanings usually

given. Many tracing boards of a Master Mason differ from the

Emulation board in their details, but five basic elements are common

to nearly all boards. These five elements will now be described with

reference to the Emulation board. The first element is an enclosing

rectangle with sides that are in the proportions of the phi ratio, which is

approximately 1.618 and

is called the Golden Section. These

proportions are mathematically and aesthetically elegant and produce

the rectangle that is most pleasing to the human eye. The derivation

and symbolism of the phi ratio are explained in the

chapter discussing tracing boards in general. The board is in

portrait form with a thick black border, oriented so that east is at

the foot of the board and west is at the head of the board. This

black border represents a grave, reminding us of our ultimate

destiny on earth. The second element is a coffin enclosed within the

grave, with its head to the west. The emblems of mortality and the

implements with which the master craftsman was slain are resting on

the coffin. A memorial tablet near the head of the coffin is

inscribed with details of the master craftsman and a record of his

death, similar to an inscription placed on the headstone of a grave.

Three Hes also are depicted on the coffin in the form

of an open triangle, with its apex to the east near the foot of the

coffin. They allude to the untimely death of the master craftsman

and are intended to remind us of human frailty.

The

third element comprises a Master Mason’s working tools. The

compasses are placed between the pencil and skirret, with its legs

extended to enclose a circle having a point at its centre. When thus

placed, the working tools remind us that during our mortal lives we

must keep our passions and prejudices within due bounds, while using

our mental and manual skills in the Lord's service. The fourth

element is a large parchment scroll placed within the triangle of

Hes and draped over most of the lower half of the

coffin, with the ends hanging down on each side. A depiction of the

interior of the first temple at Jerusalem is at the centre of the

scroll, viewed looking westwards towards the Holy of

Holies, which can be seen through the partly drawn curtains

at the western end of the Holy Place. On the

overhanging right hand side of the scroll is a brief eulogy to the

master craftsman, inscribed in Hebrew. The overhanging left hand

side of the scroll depicts an equilateral triangle near its upper

edge and near its lower edge a circle circumscribing a pentagram or

open pentacle with a Yod in the centre. Along the

bottom of the scroll an epitaph is inscribed in Hebrew, partly on

the right side and partly on the left. The scroll and its

inscriptions remind us that, at the close of this mortal existence,

all those who have faithfully served the Lord may hope to enter that

house not made with hands, the Eternal Temple in the heavens. The

fifth element is an acacia bush at the head of the grave, reminding

us that an immortal soul dwells in every mortal frame.

Before

considering the various elements of the board in detail, it would be

helpful to review the parts played by several Biblical people who

were significant, directly or indirectly, during the building of the

first temple at Jerusalem. It is important to know the Hebrew

characters and the cryptic transliterations representing these

Biblical names, as well as to understand the meanings of their

names. All of this is relevant to the inscriptions relating to the

untimely death of the master craftsman. The spellings of the names

and words that follow are from the unpointed Hebrew

characters. For convenience they are written as in English,

from left to right, but it must be remembered that in

Hebrew they were written from right to left. Of those

responsible for the construction of the first temple at Jerusalem,

the three best known are Solomon King of Israel (Shin Lamedh

Mem He, which probably means peaceful), Hiram

King of Tyre (He Waw Resh Mem, which signifies

altitude or exalted) and Hiram Abif the

skilful and experienced master craftsman whose first name is the

same as that of the King of Tyre and whose second name, Aleph

Beth Yod Waw, could signify his father.

However Abif probably was a surname, which is the

sense ascribed to it by Luther and the Swedish translators. Heinrich

Gesenius (1786-1842), an eminent German biblical scholar and Hebrew

lexicographer, says in his book Hebräisches

Elementarbuch that Abif variously signifies a

master, teacher, or chief

operator. This interpretation is supported by the modern

New English Bible translations, firstly in I Kings

7:14 which describes Hiram Abif as "a man of great skill and

ingenuity, versed in every kind of craftsmanship in bronze"

and again in II Chronicles 2:13 where he is called "a

skilful and experienced craftsman, master Huram".

In

addition to those three important persons, there are another three

Biblical characters that are of special significance to a Master

Mason. Those three are Tubal Cain, Machbanai and Adoniram. Because

Tubal Cain (Tau Beth Lamedh and Qoph Yod

Nun, usually translated as Tubal the Smith) is

one of the four founders of the crafts named in the Bible, he is

referred to in the earliest known copy of the Old

Charges of the operative freemasons, the Regius

MS of about 1390. The New English Bible

version of Genesis 4:22 refers to Tubal Cain as "the master of

all coppersmiths and blacksmiths". He is the first artificer

in metals mentioned in the scriptures. In this context there can be

no doubt that Hiram Abif, the chief worker in bronze at the

construction of King Solomon’s temple, who was responsible for

casting the two great pillars and all the lavers and other

ceremonial vessels, was indeed a master craftsmen and a worthy

successor of Tubal Cain who therefore deserved the appellation of

Master.

Machbanai (Mem Heth Beth Yod Nun Aleph Yod),

was an important person who is referred to in I Chronicles 12:13. He

was the eleventh of the band of Gadite warriors who joined King

David in the wilderness at Ziklag, in about 1002 BCE, when they

formed a mighty host and made David king over all

Israel. They routed the Philistines and recovered the Ark of the

Covenant, which they conveyed to Jerusalem. King David was then able

to begin preparations for the building of the temple at Jerusalem.

Machbenai appears in I Chronicles 2:49 as Machbenah (Mem Heth

Beth Nun He) and there are several other variations or

derivatives of the name in the Bible. They include Machir (Mem

Kaph Resh or Mem Waw Heth Yod Resh) in Genesis

1:23 and also Machi (Mem Heth Yod) in Numbers 13:15.

There are several other variations in spelling to be found in the

Revised Version and also in the Revised Standard Version of the

Bible, which illustrate the difficulties in achieving exact

translations of the old unpointed Hebrew texts. Machbanai and its

variants have several meanings, which include the

smiter that is relevant to his role as a member of the

mighty host. It can also mean the builder is

smitten and the builder (or master) is slain,

which are relevant to later events during the building of the

temple. A number of closely associated and similar sounding words

that are of special significance are discussed in the section on

significant Hebrew words.

Adoniram (Aleph Daleth Nun Yod Resh Mem,

meaning my lord is exalted) was another very important

character involved in the construction of the first temple at

Jerusalem, even though he is often overlooked. King Solomon

appointed Adoniram as the superintendent over the levy of thirty

thousand workmen from among the Israelites, who were sent in courses

of ten thousand a month to work on Mount Lebanon. The first mention

of Adoniram is in II Samuel 20:24, when as Adoram he was an

officer in charge of the tribute levied by King David. Later, in I

Kings 12:18, he is called Adoram when he was one of the officers in

charge of the levy under Rehoboam, a son of King Solomon. Rehoboam

was the last king of the united monarchy and also the first king of

the southern kingdom of Judah. Adoniram is referred to for the last

time in II Chronicles 10:18, when he was called Hadoram, the

chief officer of Rehoboam's tribute. The Bible records that when

Adoniram was sent by King Rehoboam to collect the usual taxes, the

rebellious people of the northern tribes stoned him to death, which

precipitated Jeroboam's revolt against the king in about

922 BCE. Both Adoram and Hadoram are shortened and familiar

forms of Adoniram.

We will now examine the various derivations of Machbanai and

some other closely related words with respect to their

interpretations and their relevance to the untimely death of the

master craftsman, Hiram Abif. The initial letters of the words that

comprise Machbanai and other names, as well as of other relevant

words, appear on the tracing board of a Master Mason either as

Hebrew characters or as their cryptic transliterations. As in all

languages, an interesting aspect of a study of Hebrew names and

their associated words is the uncertainty, in any particular

instance, whether the associated words came into the language as

derivatives of the name, or whether the name is composed of words

reflecting characteristics of the person. As with many English

names, either possibility might be the appropriate alternative, but

no attempt will be made in this review to allocate a probability in

respect of a particular usage. This examination is not exhaustive,

nor does it set out to assign all of the available meanings of a

name.

Several of the

more important root words and their meanings will be examined, from

which are derived the various expressions in common usage. The root

words may be examined in relation to a commonality of meaning, or to

a similarity in sound, or to a possible mistake in the reading of a

Hebrew character for one or another of the reasons already

mentioned. Sometimes these categories overlap, even though the

overlapping elements may not be immediately evident. Some relevant

words relating to building, arranged in the alphabetical order of

the Hebrew characters, are: bena meaning

to build, spelled Beth Nun Aleph;

banah meaning to build up, spelled

Beth Nun He; bonai or

b'nai both meaning a builder, spelled

Beth Yod Nun Aleph Yod; and b'nain

meaning a building, spelled Beth Nun Yod

Nun. Words relating to striking and death include the

following: mooch, which means to

kill and is spelled Mem Waw Heth. It is also

written as mooth and is spelled Mem Waw

Tau. Another is machi meaning a

smiter, spelled Mem Heth Yod. Yet another word

of similar import is machah, meaning

to destroy or to blot out, which is

spelled Mem Heth He. Finally in this context is the

similarly sounding makkah, meaning a

blow or smiting, which is spelled Mem

Kaph He. There also are several other relevant words that

have similar sounds, but have quite different meanings. They are:

maq meaning putrid or

rottenness, spelled Mem Qoph; the

interrogative mah, spelled Mem He; and

the definite article h' or ha, spelled

He. All of these words are of importance when

endeavouring to make an objective interpretation of the Hebrew

inscriptions on the scroll and the other characters that appear on

the Emulation tracing board.

Although the

several physical components depicted on the board are individually

related to one or another of four of the five elements of the

tracing board, their symbolisms are so closely interwoven that their

meanings can be understood better if they are first considered

together. Nevertheless, it is important also to consider the more

esoteric components separately. When appropriate, some of the

significant variations that appear on modern tracing boards will

also be mentioned. The physical components are the grave, the

coffin, the elements of mortality, the acacia bush, the working

tools of a Master Mason and the implements with which the master

craftsman was slain. The coffin is placed in the grave with the foot

towards the east, which has been the traditional and symbolic

orientation for burials in all beliefs and in all ages, so that the

interred body is directed towards the rising sun, which is an

ancient emblematical reference to a belief in resurrection. The

emblems of mortality are placed over the pectoral region of the body

to symbolise the departure of the spirit from the body, which is

eloquently expressed in one of the Scottish rituals:

"Look on this ruin, it is a skull

Once of ethereal

vision full.

This narrow cell

was life's retreat,

This space was

thought's ambitious seat.

What beauteous

vision filled this spot,

What dreams of

pleasure long forgot.

Nor love, nor

hope, nor joy nor fear

Has left one

trace or record here,

Yet this was once

ambition's airy hall,

The dome of

thought, the palace of a soul."

The acacia, or

shittim wood, is an evergreen and one of the few trees that can

survive the rigours of the harsh wilderness and deserts of the Holy

Land, for which reason it has been regarded as an emblem of

immortality since ancient times. Joel prophesied that in the

Day of the Lord the Valley of Shittim would receive

the life-giving water. Shittim was esteemed as a sacred wood among

the Israelites. It was used to construct the Ark of the

Covenant, the frames of the tabernacle, the table for the

shewbread and for all other sacred furniture. In the Greek language

akakos and akakon, which respectively

mean guileless and harmless, are derived

from akakia, which means acacia and in

Greek is also used as an alternative word for inosens,

which means innocence. The acacia bush at the head of

the master craftsman's grave reminds us that his virtuous conduct,

integrity of life and fidelity to the trust placed in him should be

emulated by every Master Mason. An ancient custom, still in use, is

to carry or wear a sprig of evergreen such as acacia, rosemary or

myrtle at funerals and commemorative services. Acacia is also

regarded as a symbol of initiation. A special plant became

associated with a particular rite in the ancient initiations and

religious mysteries, ultimately being adopted as a symbol of that

rite. Such symbolic plants include the lettuce in the mysteries of

Adonis, the lotus among the Brahmins, the lotus and the Erica or

heath among the Egyptians, the mistletoe among the Druids and the

myrtle in the mysteries of Greece. In freemasonry acacia is a symbol

of initiation, not as an apprentice, but into the life hereafter as

it is emblematically portrayed in the third degree. The acacia bush

reminds us that innocence must lie in the grave until the voice of

the Most High calls it to a blissful eternity.

The working tools

are placed at the head of the coffin, because the brain is the seat

of learning. The pencil, skirret and compasses invoke the mental

faculties rather than manual skills in their use. The pencil is used

by the skilful architect to define precisely the requirements for

the structure, which symbolically warns us to carry out all of our

responsibilities to God and man, as our words and actions are

recorded by the Almighty Architect to whom we must give an account

of our conduct through life. The skirret is used to mark out the

ground with accuracy for the foundation of the intended structure,

symbolically pointing out that a straight and undeviating line of

conduct is laid down in the scriptures to govern us in our pursuits.

The compasses are used to delineate exactly the limits and

proportions of the several parts of the building, to ensure that

beauty and stability adorn the completed work. The compasses

symbolise the unerring justice and impartiality of the Most High,

reminding us to keep our passions and prejudices within due bounds

because we will be rewarded or punished accordingly as we have

obeyed or disregarded His divine commands.

The

implements with which the master craftsman was slain are the plumb

rule, the level (or the square in the Irish working) and the heavy

setting maul. They are placed at the foot of the coffin to signify

that all earthly pursuits have been trampled underfoot by death. The

plumb rule and level (or square) reflect the utmost integrity of the

Master craftsman, even in the face of the gravest danger that

resulted in his death, which is signified by the heavy setting maul.

From time immemorial the heavy setting maul has been an emblem of

death by violence. The heavy setting maul is the implement used by

operative masons to set ashlars and paving stones level and to bed

them down on their foundations, from which is derived the expression

"setting to a dead level". On many tracing boards a

try square, the Master's emblem of office in speculative craft

freemasonry, is shown near the foot of the coffin to signify that

Hiram Abif died in office while serving the Lord. On some boards

three gallows squares, the emblem of office of a Master in operative

freemasonry, are depicted on the vertical face at the foot of the

coffin. Because three is regarded as the most perfect and most

sacred number, the three squares at the foot of the coffin show that

the Master craftsman had lived a blameless life, on the square with

all mankind, as he was when he departed this life. When associated

with the acacia bush at the head of the coffin, the three squares

also signify that a state of perfection can be achieved only when

the immortal spirit is raised in the life hereafter.

The

triangle formed with the three Hebrew characters He or

the three 5s has several interpretations, of which the

first is mystical. From ancient times the equilateral triangle has

been an emblem of God and a symbol of perfection. Because the apex

is pointing downwards, we are reminded that perfection can only be

achieved by passing through the Valley of the Shadow of

Death. The sum of the three Hes forming the

triangle is the mysterious and omnific 15, a sacred

number that is symbolic of the name of God. The number

15 is sacred because it is the numerical equivalent of

the Hebrew characters Yod He, which signify

Jah. This is the "two lettered" name of

God that is used in Psalm 68:4 and is usually translated as

Lord in the Bible. Most biblical scholars consider

that this "two lettered" name is a name of God in its

own right, equivalent to the Tetragrammaton. The

Tetragrammaton is spelled Yod He Waw He

and is also called the Ineffable Name, which is

transcribed in English as YHWH or JHVH

and is usually rendered as Yahweh and

Jehovah. However, some say that the "two

lettered" name of God is only a contraction of the

tetragrammaton. Because the Hebrew characters do not

include separate numerals, other characters are used as substitutes

for numerical values, the Yod representing

10 and the He representing

5. However, as a mark of respect and in veneration of

the sacred name, Yod and He are not

usually used together to represent 15, but

Teth and Waw are substituted

respectively representing 9 and 6.

The

temporal interpretation of the three Hes or

5s, commencing with the lowest and moving clockwise,

relates to the individual in his natural environment and to his

civic obligations. The first character concerns our physical

surroundings and represents the five natural forms of matter

envisaged by the ancients, which are earth, air, water, ether and

fire. The second character concerns our mental capabilities and

represents the five human senses by which we perceive our

environment, these being feeling, hearing, seeing, tasting and

smelling. The third character concerns our moral responsibilities

that are represented by the five points of fellowship, which are to

meet a brother on the square and sustain him when in difficulty or

danger, to support him in his virtuous and laudable undertakings, to

pray for him and assist him in his times of need, to keep inviolate

his private affairs and lawful secrets and to vindicate his

reputation with as much sincerity in his absence as in his

presence.

There

also is a collective interpretation of the three characters that is

of particular interest to speculative freemasons. The three

Hes are the initial letters of the three Hirams who

assisted King Solomon in the design, supply of materials and

erection of the temple. They were Hiram King of Tyre, Hiram Abif and

Adoniram, who are included in the important biblical names already

discussed. The characters also refer to the fifteen trusted

craftsmen who, in masonic legend, were chosen by King Solomon to

make a diligent search for Hiram Abif when he had disappeared from

his place of work at the temple. The craftsmen were formed into

three lodges of five and went forth in different directions,

acquitting themselves in their various duties with the utmost

fidelity. When the body of the Master craftsman was found it was

recovered and conveyed to Jerusalem, where it was interred as near

to the Holy of Holies as Israelitish law would permit.

Finally, the three characters represent the five perfect

points of entrance in each of the three speculative degrees of

freemasonry, which are preparation, obligation, sign, token and

word. Test questions on the perfect points of entrance can be traced

back to the catechisms used by the operative freemasons, with whom

they comprised an essential part of the instruction received. The

perfect points of entrance are included in the earliest known

speculative ritual, the Edinburgh Register House MS of

1696, which contains a description of the Scottish ceremony for the

initiation of an Apprentice. They also appear in the Dumfries

No 4 MS of about 1710 and in the Trinity College,

Dublin MS of 1711. The test questions are used more

extensively in the Scottish and Irish workings than they are in the

English workings.

Immediately above

the emblems of mortality is a memorial inscription, similar to those

that appear on the headstones of graves. The Roman numerals on the

plaque are the clue to deciphering the cryptic characters. It is

immediately evident that the numerals are intended to be read from

right to left, as the Hebrew characters would have been written, but

it may not be so evident that in fact they are seen as a mirror

image. If all of the cryptic characters are visualised as being read

from within the coffin, then they are readily decipherable as

standard characters that were used in most of the old treatises on

masonic scripts. From time to time writers have said that they have

found errors in the script, which they have blamed on Brother John

Harris's transcription, but those claims seem to have been based on

a false premise, especially as some of the cryptic characters are

the same whether read from within the coffin or from outside. In the

following comments all characters that are written from left to

right must be visualised as they appear in the inscriptions, which

is from right to left.

The three

characters above the date are the equivalent of He Aleph

Beth and refer to Hiram Abif. The date is shown as

AL 3000, which is a reference to the Latin

Anno Lucis meaning "in the Year of

Light", calculated by adding 4,000 to the years BCE

(Before Common Era). In 1650 Archbishop Ussher dated

the creation of the world and the appearance of Adam at

4004 BCE, which was rounded off when determining the Year

of Light. On the basis of the then available knowledge for

dating Biblical events, King Solomon’s temple was nearing completion

in about 1000 BCE, or AL 3000, when the master craftsman

was slain. Modern research indicates that the date probably would

have been about 950 BCE, or AL 3050, but the difference is

of no consequence in relation to the legend. On most modern boards

cryptic characters equivalent to Tau and

Qoph are placed to the right and left of the plaque

respectively, but preferably they should be at the head of the

coffin, each side of the working tools as on the Emulation board.

The Tau and Qoph are the initials of

Tubal Cain, who was sent to King Solomon as the Master Smith,

although his duties became much wider in scope. There is no Hebrew

character for C, but the sound derived from the

initial Qoph of Cain has been transliterated as a

C in the cryptic characters.

Immediately below

the emblems of mortality, reading from right to left, there are

cryptic characters equivalent to Mem Beth, which

appear twice on the Emulation board, but only once on some modern

boards. On the Emulation board and in English lodges that derive

from the Antients, as well as in all Scottish lodges,

these characters allude to the first words spoken when the

indecently interred body of Hiram Abif was discovered. The first

pair of characters allude to an exclamation of shock that was spoken

in Hebrew when the body was discovered: "Mahhah

b'nai?" spelled "Mem He, He, Beth Yod Nun Aleph

Yod", the equivalent in English being: "What! Is this

the builder?" In the Irish and also in some Scottish

workings this is expressed as "Alas, the builder!"

whilst in some Scottish workings "The death of the

builder!" is used less correctly. The second pair of

characters allude to an expression of distress: "Machi

b'nai!" which is spelled "Mem Heth Yod, Beth Yod Nun

Aleph Yod", equivalent in English to "The builder is

smitten!" The Jacobite masons in Scotland must have noticed

that the Hebrew pronunciation of this comment is almost identical to

the Gaelic "Mac benach", from Mac which

means son and bennaich which means

to bless, hence signifying "the blessed

son", an enigmatic title that the Stuart freemasons applied

to their idol, the Young Pretender. The close

relationship between Scotland and France under the Auld

Alliance is illustrated by an equivalent expression in the

French Rite, said to mean "He lives in the son!" which

cannot be derived from the Hebrew.

In their book

entitled The Hiram Key, Christopher Knight and Robert

Lomas propose another interesting derivation for the exclamations,

which they relate to the murder of Seqenenre Tao II, a Theban king

of Egypt, in about 1600 BCE. They suggest that the words come

from the Egyptian "Ma'at-neb-men-aa" and

"Ma'at-ba-aa", meaning "Great is the established

Master of Freemasonry" and "Great is the spirit of

Freemasonry" respectively. In this context

they say that Ma'at has been translated as

Freemasonry because there is no other modern single

word that conveys the multiplicity of ideas of the Egyptian word,

which they sum up as being "truth, justice, fairness, harmony

and moral rectitude as symbolised by the regular purity of the

perfectly upright and square foundation of the temple".

Ma'at is used in this context in the pyramid texts. It

might be tempting to assume that the circumstances are too remote

for such an origin to be feasible, were it not for the fact that so

much of our modern English language has been derived progressively

through a series of different languages over several millennia,

especially words and expressions relating to the liberal arts and

sciences and to religious and esoteric subjects generally.

English rituals

derived from the Moderns, as well as some American

rituals of similar origin, use a different Hebrew pronunciation for

the first exclamations made by the Fellows of the Craft who

discovered the body of Hiram Abif, based on two Hebrew verbs of

similar pronunciation. Those words are mookh spelled

Mem Waw Heth and makkah spelled

Mem Kaph He, which respectively mean to

kill and to smite, whence are derived the

exclamations "The master is slain!" and "The

builder is smitten!" These versions appear to have been

introduced by the Moderns in about 1730, to

distinguish them from the Antients who retained the

original words and whose rituals and customs differed little from

those of their Irish and Scottish brethren. Another version of the

exclamation used in some English and American workings comes from a

similar sounding Hebrew noun, maq spelled Mem

Qoph and meaning rottenness, whence the

expression "He is rotten!" and the more fanciful

"rotten to the bone", which clearly is a play on words

incorrectly combining Hebrew and English.

There is ample

evidence that, prior to the union of the Antients and

Moderns early in the 1800s, the Moderns

were only using one word, even though the Antients

were using the two words that had always been used by their Irish

and Scottish brethren. The original word used by the

Moderns was based on the Hebrew makkah,

spelled Mem Kaph He, meaning a blow or

smiting, but it appeared later with many different

spellings and pronunciations. The earliest known version appears in

the Sloane MS of about 1700, when it seems that only

two degrees were being practised in England. Four versions of the

word were in use by the end of 1725 and at least eight by 1763, but

in all there have been at least sixteen versions of the word. There

is little doubt that almost all of them were either fanciful

corruptions or mispronunciations of the various Hebrew words we have

examined. The union of the Antients and

Moderns more or less stabilised the usages, whilst

permitting the distinctions already mentioned.

An important

feature of the Emulation tracing board is a scroll draped over the

lower half of the coffin, in the middle of which is depicted an

interior view of the temple. This view is usually shown in miniature

near the middle of the coffin on other boards. The views vary in

detail, but contrary to I Kings 6:14-35 they all show a series of

columns around the interior walls. These columns probably were

included as symbols, possibly representing the five noble orders of

architecture and hence the work for which the master craftsman was

responsible, but no explanation is given in the old catechisms or in

modern rituals. On the Emulation board the ceiling of the Holy

Place is flat as described in the Bible, but on other boards

it usually is arched. The Emulation board shows a continuous series

of small arched windows along the walls of the Holy

Place, near the ceiling, which would have provided the only

light as it is recorded in the scriptures. Most other boards show a

series of arches supported on columns along the full length of the

Holy Place, but without windows, although the

Holy of Holies at the western end appears to have a

flat ceiling, as in the Biblical description.

On all tracing

boards the curtains at the western end of the Holy

Place are partially open, which reveals the Holy of

Holies and permits a glimpse of the Ark of the

Covenant and the Cherubim guarding it. Some

boards depict a priest standing in front of the entrance to the

Holy of Holies. The floor of the temple is not shown

overlaid with gold as described in I Kings 6:30, but is depicted

symbolically as a mosaic pavement of black and white tiles. On most

modern boards the first arch is inscribed with characters that

usually are indecipherable, although they are supposed to replicate

the eulogy and epitaph on the scroll of the Emulation board. The

representation of the temple on the board is explained beautifully

in another Scottish ritual:

"The

great lesson conveyed to us symbolically by this board, by the

coffin enclosing all within its cold embrace, is that at that very

moment, even from death itself springs life immortal. Here in the

bosom of death we see the mosaic pavement typical of life; not life

traversed by toil and difficulty, as formerly represented by the

winding stair, but of life eternal, triumphant over death, leading

directly through the porch to the Holy of Holies. Observe the dormer

window, emblematically admitting the revelation of divine truth; but

it is one of the most beautiful and at the same time one of the most

mysterious doctrines of masonic symbolism that the Freemason, whilst

always in search of truth, is destined never to find it in its

entirety. That teaches him the humiliating but necessary lesson that

the knowledge of the nature of God and of man's relation to Him,

which knowledge constitutes divine truth, can never be acquired in

this life. Such consummation only comes to him when he has passed

through the gateway of death and stands in the court of light, with

the full light of revelation upon him."

A eulogy, written

in basic unpointed Hebrew characters, is on the overhanging right

hand side of the scroll. It relates to the inscriptions on the

coffin. An epitaph, written in basic unpointed Hebrew characters, is

at the bottom of the scroll and also relates to the inscriptions on

the coffin. As the original texts of the inscriptions are not

available, an interpretation of the Hebrew characters on the tracing

board must suffice. This presents some difficulties because, even on

the largest tracing boards, some of the Hebrew characters lack

clarity and definition, so that they cannot be read with certainty.

It might be supposed that it was not intended that the inscriptions

should be read, but this would not be in keeping with the meticulous

care taken in other details and the interrelationship of all

components of the tracing board. As the script is composed only of

root words without vowels, prefixes or suffixes, its interpretation

is limited to character recognition for word definition and for

grammar. The interpretation of modern Hebrew writing is assisted by

vowels, prefixes and suffixes.

Because the

script on the tracing board is comprised of root words as in the

original Biblical writings, a different interpretation of a

character may allow an alternative composition of the root word.

Unless they are carefully written, it is possible to confuse several

pairs of Hebrew characters, of which the following are of particular

relevance to the inscriptions on the scroll. Yod,

Waw, Zayin and also Nun,

in the forms that are used at the end of a word, could easily be

confused if poorly written. Several pairs of characters,

Beth and Kaph, Daleth and

Resh, Gimel and Nun, as

well as Mem and Samech, are similar in

shape. Three other characters that are of the same general shape are

He, Heth and Tau, which

could easily be misread if poorly written, because the left leg of

He does not quite join the top as in

Heth, while the left leg of Tau has a

slight curve at the lower end. We do not know if Brother John Harris

correctly transcribed all of the characters from the original scroll

on Brother Josiah Bowring's tracing board, or if the original itself

included any errors.

A study of the

script shows that a few small differences in the interpretation of

characters could produce interesting changes in the translations of

the eulogy and epitaph that are worth mentioning, though none alters

their underlying meanings. A Hebrew sentence with an active or

finite verb usually commences with the verb, followed by the subject

and then the object. Passive verbs are usually omitted when a word

links the subject to the predicate that then follows. Several

interpretations have been considered, but some clearly are not

relevant to the circumstances. The root words and their relevant

meanings for the adopted interpretations are set out below in the

sequence in which they appear on the scroll. The interpretations

give the exact meanings of their Hebrew counterparts, although

equivalent modern English words could have been substituted, for

which there are other Hebrew words. For example

extremity is used with its ancient connotation of

death, as intended in extreme unction.

The alternative expressions are familiar and may have been avoided

deliberately.

The first line of

the eulogy appears to be Heth Yod meaning by the

life of and Kaph Lamedh meaning

wholly, completely, to be

finished. The second line appears to be Resh Heth

Shin meaning to give up or to throw

up followed by Lamedh Beth meaning

life or the heart or the vital

principle. The third line appears to be Shin

Resh meaning violence,

destruction and Aleph Lamedh meaning

unto, into or causation.

The fourth line looks like Sadhe Yod Resh meaning

to go or to prepare for a journey. The

fifth line is like Aleph Beth meaning

father and Yod meaning to.

If this is the correct interpretation of the characters, then the

eulogy may be expressed in the words: "Having given up his

life as a result of violence, he has passed on to the

Father." There

is no doubt that the first character in the first line of the eulogy

is Heth, but if it should have been He

then the first line actually becomes a significant noun and the

structure of the sentence is altered. The alternative translation of

the first line then becomes He Yod Kaph Lamedh, which

means the temple and in Hebrew usage specifically

the temple of the Lord at Jerusalem. However, the

structure of the sentence and its interpretation would only make

sense if the inscriptions in cipher at the head of the coffin were

included. As the ciphers originally were in Hebrew characters their

inclusion might have been intended and the eulogy would read:

"Hiram Abif, the Master Smith at the temple of the Lord at

Jerusalem, gave up his life as a result of violence and has passed

on to the Father." In all of the circumstances this is the

preferred interpretation.

The epitaph

The part of the

epitaph on the right of the scroll seems to begin with Beth

Heth meaning to rest, followed by He

Waw meaning alas!, then by Qoph Sadhe

Resh meaning extremity and finally

Beth meaning in. The part of the epitaph

on the left side of the scroll appears to be Yod Kaph Shin

Resh meaning right, proper, or

to be acceptable, followed by Heth Yod

meaning to live, then by Nun Aleph

which is an exhortation when following a verb, then by Sadhe

Beth meaning glory, splendour or

beauty and finally Yod meaning

in. When read together, these two parts of the epitaph

testify to a belief in the resurrection, saying: "Alas! He is

at rest! In his extremity may he be acceptable to live in

glory!"

Although the

portion of the epitaph on the right of the scroll clearly ends with

Beth, the two or possibly three characters preceding

it are not very clear. Their interpretation can affect the sentence

structure and also the interpretation of the preceding characters.

The first two characters clearly read Beth Heth, which

means to rest, but the next two characters He

Waw, which usually signify a lamentation such as

Alas! could signify a possessive pronoun such as

his in a different context. If only two characters

precede the final Beth, the last root word on the

right of the scroll might then be interpreted as Qoph Sadhe

Beth, which means to cut off, to cut

down, extremity or end. The

intermediate character or characters are the most obscure and might

be interpreted as Qoph Teth Beth, with similar

meanings to Qoph Sadhe Beth, but also meaning

destruction. If on the other hand the obscure writing

represents three characters, which seems likely, other

interpretations are possible for what would then be the root word

preceding the final Beth on the right of the scroll.

One is Qoph Beth Resh, the usual noun for a

grave, a burial place or a

sepulchre as well as the verb to bury; another

is Qoph Sadhe He meaning to cut off or

to destroy; and lastly there is Qoph Beth

Lamedh meaning to kill or to

slay. It is interesting that all of the alternative nouns

and verbs would be appropriate to the general tenor of the epitaph,

but grammatically the noun is to be preferred. The preceding

He Waw then becomes a possessive adjective and the

final Beth becomes an idiomatic preposition, so that

the epitaph would then read: "At rest in his grave, may he in

his destruction be acceptable to live in glory."

The symbols on the scroll

On the left hand

side of the scroll, immediately above the epitaph, a pentacle

circumscribed by a circle has a Yod in the centre,

signifying the omnificence of God. The pentacle represents man and

the single point directed heavenwards represents his integrity and

goodness. Operative freemasons considered the pentacle or pentagram

to be a symbol of deep wisdom and it is found among the

architectural ornaments of most religious structures of the Middle

Ages. Among speculative freemasons the pentacle is an emblem of the

five points of fellowship, which typifies the bond of brotherly love

that should unite the whole fraternity. The pentacle, circle and

Yod combine to herald a victory in death and a

resurrection in the hereafter by the grace of God. At the top of the

scroll, above the pentacle, an equilateral triangle with its point

uppermost signifies perfection. From time immemorial the equilateral

triangle has been used almost universally as a symbol of the Deity.

The pentacle and the Yod within a circumscribing

circle, when coupled with the equilateral triangle, indicate that as

the master craftsman, Hiram Abif, had completed his earthly labours

in the service of the Lord, he would return to his Maker and receive

his reward in life eternal. Thus the symbols on the left hand side

of the scroll aptly sum up the message that is conveyed by the

inscriptions on the coffin, in conjunction with the eulogy on the

right hand side of the scroll and the epitaph at the bottom of the

scroll.

Interpreting the Hebrew inscriptions

Those who wish to examine the foregoing interpretations in

greater depth may need more information on sentence structure, verb

forms and nouns, for which purpose the Introductory Hebrew

Grammar by R. Laird Harris is a useful reference. The

Analytical Hebrew and Chaldee Lexicon by Benjamin Davidson

is an invaluable source of information for a detailed study of

Hebrew words used in the Bible. It is arranged alphabetically and

includes every word and inflection used in the Old Testament, as

well as identifying where each word is used. Other useful references

for the derivation of significant Hebrew words and for Biblical

history relevant to this discussion are The New Bible

Dictionary published by the Inter-Varsity Press,

Unger's Bible Dictionary by Merrill F. Unger and a

book edited by John Bowker entitled The Oxford Dictionary of

World Religions. A book by Roy A. Wells, entitled Some

Royal Arch Terms Examined, also is very informative

concerning the derivation and meaning of many Hebrew words relevant

in freemasonry. He also comments on the Gaelic interpretation of one

of the words, but in doing so he misses one vital point. The word

itself certainly was not one that had been coined by the Jacobite

freemasons in Scotland, but the very close similarity of its

pronunciation in Hebrew and Gaelic no doubt gave rise to its special

connotation when used in Scotland and France.

back to top |

![]()