The

Four Tassels, that are referred to near the end of the

lecture on the first tracing board in various rituals,

are important ornaments of the lodge. They are of great antiquity

and their symbolism deserves further explanation. In fact the

symbolism of the Four Tassels, which has its origins

in operative freemasonry, is of great importance and its omission

from many rituals, or only the briefest of references to it in other

rituals, is surprising. In earlier times explanations of the origin

and deep symbolic meaning of the Four Tassels were

often given, but nowadays they are so rarely mentioned that many

speculative freemasons, if not most, are unaware of their

significance.

The

Four Tassels, that are referred to near the end of the

lecture on the first tracing board in various rituals,

are important ornaments of the lodge. They are of great antiquity

and their symbolism deserves further explanation. In fact the

symbolism of the Four Tassels, which has its origins

in operative freemasonry, is of great importance and its omission

from many rituals, or only the briefest of references to it in other

rituals, is surprising. In earlier times explanations of the origin

and deep symbolic meaning of the Four Tassels were

often given, but nowadays they are so rarely mentioned that many

speculative freemasons, if not most, are unaware of their

significance.

References

in modern rituals

The

following reference to the Four Tassels, which is

taken from the English Emulation Ritual, is very

similar to the references found in many other English and Scottish

rituals and some Irish rituals and their derivatives around the

world, probably is better known than most:

“Pendent

to the corners of the Lodge are four tassels, meant to remind us of

the four cardinal virtues, namely: Temperance, Fortitude, Prudence

and Justice, the whole of which, tradition informs us, were

constantly practised by a majority of our ancient

Brethren.”

The

concluding portion of that quotation is the only inkling that is

given of the operative origin of the Four Tassels and

their significant symbolism. Whilst the reference to the four

cardinal virtues should stimulate constructive thought, no

explanation is given to associate the tassels with the corners of

the lodge and there is no apparent reason for them to be there.

Moreover, as the concluding portion of that quotation has been

omitted from many versions of the ritual, the origin and

significance of the Four Tassels has become even more

obscure.

In

the Scottish A.S.MacBride Ritual reference to the

Four Golden Tassels is made in relation to the

ornaments of the lodge in the explanation of the plan

or tracing board, which is quite a brief charge. Many

of the American and several of the English, Irish and Scottish

rituals do not include extended lectures on the tracing

boards, but describe much of the relevant symbolism in a

series of charges. In the Scottish Modern Ritual the

first lecture on the tracing boards concludes with the

following statement, which is somewhat unusual and probably has its

origins in the rituals of some lodges on the continent of

Europe:

“You

will see that our carpet has a tessellated border, which represents

the divine protection encircling humanity, whilst the four tassels,

which ornament its corners, denote prudence, temperance, fortitude

and justice.”

Before

explaining the operative origins of the Four Tassels,

it would be appropriate to consider the lecture on the first

tracing board included in the English Revised

Ritual, which was originally written during the 1800s, has

been under continual review ever since and has received high praise

from many distinguished brethren. In nearly all of its aspects this

ritual is indeed a beautiful exposition of the rites and symbolism

of speculative craft freemasonry, but the following section relevant

to the Four Tassels, which is quoted from the sixth

edition printed in 1962, brings into sharp focus some of the

misconceptions on the subject:

“The

two Ends of the Lodge, facing severally due East and West, and the

two sides, facing respectively North and South, thus indicating the

four cardinal points of the compass, represent to us the Four

Cardinal Virtues, namely, Temperance, Fortitude, Prudence, and

Justice.”

Moreover,

the lack of knowledge on the subject is highlighted by the footnote

in the ritual relating to the passage, which says:

“The

allusion sometimes made to four tassels is misleading; very few, if

any, Lodges have any such thing, and they could serve no useful

purpose if they had. No symbolical meaning is given to them

anywhere.”

It

is remarkable that the mistaken beliefs and indeed the lack of

understanding that these two passages reflect in relation to such a

fundamental aspect of masonic symbolism have not been noticed and

corrected for so long a time, especially as it is not very difficult

to seek out the correct information.

Before

explaining the operative origins of the Four Tassels,

it would be appropriate to consider other cords and tassels often

depicted on tracing boards and surrounding the mosaic pavement,

which refer to the protective care of the deity and the uniting

bonds of the fraternity. Although the origin and symbolism of those

cords and tassels are not the same as those of the Four

Tassels, they also were in use before the advent of modern

speculative freemasonry and the two symbolisms are often confused.

Comprehensive explanations of the symbolism of the surrounding cords

and tassels are given in various old rituals from the continent of

Europe, at least the elements of which are still explained in their

catechisms.

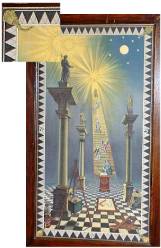

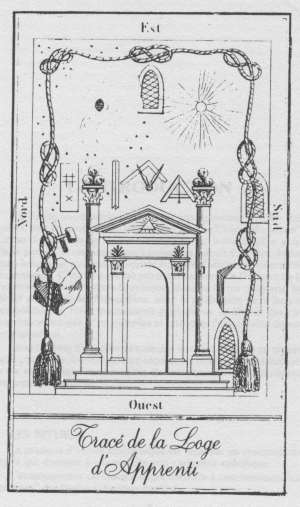

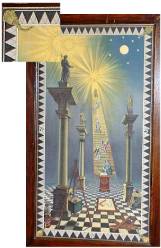

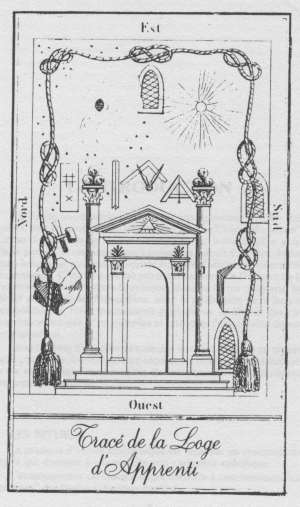

Some

early tracing boards of the first degree were enclosed

within a continuous wavy cord that was knotted at the four corners

and terminated with its two tasselled ends hanging down. In French

lodges this arrangement of the cord is called la houppe

dentelée, which means “the scalloped tassel”

and is described as “a cord forming true-lovers’

knots”. The old French ritual explains that the cord should

remind all freemasons that the bonds uniting them should draw them

closer together, irrespective of the distances that may separate

them. In German lodges the knotted wavy cord is called die

Schnur von starken Faden, which signifies “a cord of

strong threads”. The old German ritual also explains that

the cord symbolises the fraternal bond by which all freemasons are

united.

Also

relevant to this discussion are the comments of Dr John I. Browne in

the Master Key, which sets out the elements of the

Prestonian lectures. He says that the wavy cord and tassels allude

to “the kind care of Providence which so cheerfully surrounds

and keeps us within its protection whilst we justly and uprightly

govern our lives and actions by the four cardinal virtues in

divinity”. Alternative English translations of

dentelée are “serrated” and

“indented”, whence the “indented border”

has been derived. On the other hand “tessellated” is

not a derivative of houppe, but comes from the Latin

tessella, which is the diminutive form of the Latin

tessera and means “a small four-sided

tile”.

From

the foregoing it is evident that the “indented or tessellated

border” of black and white triangles, which usually

surrounds the mosaic pavement on the lodge floor and

also the first tracing board, is not the same as the

knotted and tasselled wavy cord that represents the divine

protection encircling humanity. Nor is the “indented or

tessellated border” the same as the bonds that unite the

members of the fraternity and should draw them closer together. As

mentioned earlier, the modern indented or tessellated border is

primarily an ornament that alludes to the celestial sphere of our

existence. However the tassels depicted at the four corners of most

tracing boards of the first degree, which among other

things is a representation of the lodge room, do refer to the four

cardinal virtues.

All

speculative freemasons are or should be aware that, symbolically,

they are intended to find the answers to their questions on

the centre, which is that point within a circle from which

all parts of the circumference are equally distant. The Point

within a Circle is an ancient and sacred hieroglyph that

refers to the deity. It is a symbol of sufficient importance to

merit thorough contemplation, but it will suffice now to say that

answers found on the centre are those established in

accord with the decrees of the deity. Many speculative freemasons

may not be aware that, down through the ages, all significant

religious structures and other stately edifices have been set out

from the centre, because such structures should be

located having a proper regard for the position they will occupy in

the civilised society in which they will fulfil an essential role.

Their position and form therefore are expected to reflect their

importance and their significance. Thus in ancient times a temple

often was located on the site of an earlier sanctuary, place of

offering, sacred site or memorial stone. A cathedral likewise has

often been located on the site of an earlier religious structure or

a succession of structures like the York Minster, to perpetuate the

sanctity of the site. For this reason it usually was considered

important for the centres of the old and new structures to be the

same.

In

operative times, when the location of the centre of an intended

structure had been decided, the master mason’s first duty was to

establish the centre point of the structure on the site. This was

referred to as striking the centre. He would then

determine the required orientation of the building by an appropriate

method and set it out on the ground. Sacred buildings usually were

required to face either due east or the rising sun at the summer

solstice. If the required orientation was to be due east to west,

the first step was to determine the true north-south line

accurately, from which the true east-west line could be set out. In

the northern hemisphere either due north could be determined by

sighting the pole star at night, or due south could be determined by

marking the direction of the sun at noon at either of the equinoxes.

As there is no pole star in the southern hemisphere, it is necessary

there to determine due north by marking the direction of the sun at

noon at either of the equinoxes. In both hemispheres the correct

orientation at the summer solstice could be ascertained by direct

observation of the sunrise at that time.

In

the northern hemisphere the true north-south line can be determined

by setting up a plumb line over the established centre point and

then aligning two other plumb lines with the pole star and the plumb

line over the centre point, the other two plumb lines being placed

one each at convenient distances outside the northern and southern

boundaries of the building. The north-south line can then be set out

on the ground by stretching a string line between the two outer

plumb lines and passing through the centre point. The true

north-south line in both hemispheres can be determined at either

equinox by observing the sun’s shadow from about two hours before

noon until about two hours after noon. When two or preferably three

concentric arcs of sufficient length have been marked out on the

ground, using the line from a skirret that has been set up at the

centre point, a perpendicular rod of sufficient height is erected at

the centre point. The several points where the end of the sun’s

shadow just touches each of the arcs, as the shadow shortens and

again as it lengthens, are then marked on the ground. A line from

the centre point to the point on each arc that bisects the distance

between the two points on that arc, where the sun’s shadow just

touches the arc, indicates the true north-south line. It is

desirable to use several consecutive arcs in this observation, in

case the sun is obscured when the end of the shadow would just touch

the arc, as well as to confirm the accuracy of the several

observations. It also is desirable to carry out the observation on

three consecutive days, including the day before and the day after

the equinox.

When

the true north-south line had been determined, it was accurately set

out on the ground by means of a string line through the centre

point, from which the true east-west axis was also set out on the

ground. The east-west line can be set out from the north-south line

with the aid of three long rods having lengths of three, four and

five units, with which a right-angled triangle can be formed. As a

check for accuracy, right-angled triangles should be assembled on

both the left and the right of the east-west line and the procedure

should be carried out both to the east and to the west of the

north-south line. When assembling the triangles it was customary to

place the side three units long against the north-south line, so

that the side four units long indicated the east-west line. A more

accurate method of setting out the east-west line is to use two

skirrets, which are set up at two points on the north-south line

that are equidistant from the centre and as far apart as

practicable. The lines from the skirrets are then extended

sufficiently to intersect on the east-west line where, for accuracy,

their angle of intersection should be approximately a right angle.

As a check for accuracy this procedure should be carried out both to

the east and to the west of the north-south line. If carried out

properly the line between the two points where the skirret lines

intersect is the east-west line, which should pass through the

centre point.

When

the centre point of the building and the two main axes passing

through the centre point had been established, the next step in

setting out was to establish the four points of a rectangle to

delineate the four corners of the principal constituent of the

building. When setting out a cathedral, for example, these four

points would define the corners of the nave. The setting out of

subsidiary components, like the transepts and the chapter house,

usually could be deferred until an appropriate time during

construction. The axes of the nave and the transepts of York Minster

and many cathedrals in the Gothic style intersect at the centre

point of the structure, but this arrangement is not always adopted.

For example the Salisbury Cathedral has two transepts, although the

axis of the main transept does pass through the centre point. In

France the plan of the nave and transepts in some cathedrals is in

the form of a Latin cross. The three traditional shapes for temples

are the square; the oblong-square in the proportions of two to one;

and the temple-square in the proportions of three to one, like King

Solomon’s temple in Jerusalem. Although the principal constituents

of religious structures are predominantly rectangular in plan, other

shapes also are used. These include the octagon adopted for most

chapter houses attached to churches and cathedrals, which were

usually constructed in the style used by the Knights Templar. The

octagon was also used frequently in Byzantine churches. The circle

was adopted for the Pantheon constructed in Rome by Hadrian as the

temple of the gods, which is now the church of Santa Maria Rotonda.

Sometimes a circular interior has been combined with an exterior

that is square or octagonal, or occasionally an even more complex

shape.

The

points established to locate the four corners of the principal

constituent of the building were also set out from the centre point.

This was achieved by fixing a skirret at the centre point, from

which a line of the required length could be extended to each of the

four corners in succession. The required direction of each of these

diagonal lines was a function of the shape of the principal

component of the building. It was one of the duties of the master

mason to determine the required directions, which he then set out

with reference to the north-south and east-west axes that had been

established through the centre. The diagonals were set out using the

three long rods, each of which was appropriately graduated to enable

the required angles to be measured with reference to the main axes

of the building. The method was similar to that used when setting

out the east-west axis from the north-south axis, except that the

right-angled triangle formed by the three rods was rotated by the

required amount. Having marked the four corners, the accuracy of the

rectangle was checked by comparing the measurements of the two ends

and the measurements of the two sides. When the four corner marks

had been established, distinctively marked perpendicular stakes were

set up near them, drawing attention to their location and protecting

them from inadvertent damage. Suspended coloured cords or streamers

distinguished the marker stakes, in the same way as brightly painted

stakes or stakes with coloured bunting are used to indicate

important survey marks in the present day.

The

four tassels pendent to the four corners of the lodge,

that are referred to in lectures on the first tracing

board, are directly related to the methods used by the

operative master masons when setting out the four corners of the

building and also when constructing the corners in stonework. The

relationship between the four tassels and the setting

out of the building is immediately evident from the foregoing

description of the methods used, but their relationship to

construction of the building may not be so evident. When

constructing the corners of the building plumb lines were suspended

from timber supports adjacent to the corners, to ensure that the

corners were perpendicular as well as being correctly located in

relation to the established corner marks. Lines were also strung

between the relevant plumb lines at the corners, to ensure that the

walls followed the correct lines to ensure that the corners were

square as well as perpendicular. The four tassels also

allude to the plumb lines that were set up at the corners of the

building during construction.

In

operative times the four tassels that were suspended

in the four corners of the lodge room represented guides, which were

intended to assist a freemason to maintain a just and upright life,

whence was derived the reference to the four cardinal virtues that

traditionally are temperance, fortitude, prudence and justice. In

modern speculative lodges those four tassels,

respectively representing temperance, fortitude, prudence and

justice in that sequence, should commence in the southeast corner,

which is on the Worshipful Master’s left hand side, then proceed

clockwise around the lodge room. Nowadays tassels are not a common

feature in lodge rooms, but are usually represented only by the name

of one of the four cardinal virtues in each corner. In some lodge

rooms the name is shown on a decoration representing a tassel

attached to a short cord, which sometimes is incorrectly depicted as

a loop. In other lodge rooms the only representations of the tassels

are those that appear at the corners of the first tracing

board. As mentioned earlier, the cords and tassels that are

often incorporated into the tessellated border surrounding the

mosaic pavement have a different origin, even though in some rituals

they are said to represent the four

tassels.

Before

considering in which corners the four tassels would

have been suspended in an operative lodge room, it would be

appropriate to review what the four cardinal virtues signify. In

modern everyday language temperance suggests

moderation or even abstinence;

fortitude implies courage in endurance;

prudence conveys an impression of cautious

self-interest; and justice implies the

awarding of what is due. Whilst all of these definitions

reflect important characteristics that are relevant to the

principles esteemed in freemasonry, they do not embrace all facets

of importance in masonic conduct. For example, in freemasonry

temperance requires the exercise of caution in

thought, judgment, feeling, speech, act and deed in every aspect of

life and work. The practise of temperance must be closely allied

with fortitude, which implies moral courage as well as

physical bravery, which requires a freemason to pursue the course

that he knows to be right, even if in so doing he meets unforseen

problems and the outcome is not what he had anticipated. Even so,

the pursuit of the right course of action must always be tempered

with prudence, which involves the use of common sense

and the proper application of reason and logic. In commonplace usage

justice implies a strict interpretation of the law,

but in its broader sense it should reflect the greatest good for the

community as a whole. In freemasonry justice is always

allied with mercy. This is why, in many versions of

the lecture on the first tracing board, the reference

to the four cardinal virtues is followed immediately by a statement

similar to the following passage quoted from the English

Emulation Ritual:

“The

distinguishing characteristics of a good Freemason are Virtue,

Honour, and Mercy, and may they ever be found in a Freemason’s

breast.”

In

this context mercy implies that justice

alone is insufficient, but that it must be tempered by

mercy if an equitable outcome is to be achieved. By

definition mercy means forbearance towards anyone who

is in one’s power, but in a parallel sense it is considered to be

something good that is derived from God. Virtue and

honour are important corollaries of mercy.

Virtue signifies goodness, morality and probity and

also implies the many attributes of honour, which in

turn signifies honesty, integrity, rectitude and uprightness.

As

operative lodges were oriented in the same direction as King

Solomon’s temple at Jerusalem, which is the reverse of modern

speculative lodges, the entrance to the lodge was in the east and

the master was seated in the west. To avoid possible confusion, in

the following discussion reference will be made to the positions of

the officers’ stations in the lodge, not to the compass points.

Operative lodges had a Master, a Senior Warden and a Junior Warden

who were located with respect to each other, except for the compass

orientation, similarly to the stations of those officers in modern

speculative lodges. In operative lodges there also was a fourth

officer, the Superintendent of Work, whose location was on the

opposite side of the lodge from the Junior Warden. In this

explanation of the location and symbolism of the four

tassels pendent from the corners of the lodge, all four of

these officers are assumed to be seated facing inwards towards the

centre of the lodge.

The

tassel in the corner on the Master’s right hand side should

represent justice and that on his left hand side

should represent temperance. The reason for this is

that, when ruling in his lodge and managing his work force, the

Master should rule with justice that nevertheless must

be tempered with mercy, so as to ensure that not only

will the client obtain the service he is paying for, but also that

his workmen will receive their just dues. The tassel in the corner

on the Superintendent of Work’s right hand side should represent

prudence and that on his left hand side should

represent justice. Like his Master, whom he

represents, the Superintendent of Work must be prudent

in the use of his work force and the materials, so that the Master

is properly served; but he must also ensure the men are treated with

justice so that they receive the dues to which they

are entitled.

The

two Wardens are the officers who exercise direct control over the

workmen, under the immediate supervision of the Superintendent of

Work. The tassel in the corner on the right hand side of the Senior

Warden should represent fortitude and that on his left

hand side should represent prudence. The reason for

this is that, as the officer who exercises direct control over the

workmen while they are at labour, he is responsible for overcoming

the many difficulties that inevitably will beset the work, which

will require the utmost fortitude on his part. At the

same time he must exercise his control over the men’s employment and

the use of materials with the utmost prudence, to

protect the men’s welfare whilst at the same time ensuring that the

workmanship cannot be faulted. The Junior Warden, whose duty it is

to assist the Senior Warden, is the officer primarily responsible

for the men’s welfare especially when they are at rest and

refreshment. The tassel in the corner on right hand side of the

Junior Warden should represent temperance, in allusion

to the manner in which refreshment should always be conducted. The

tassel on the Junior Warden’s left hand side should represent

fortitude, because he is supposed to personify Hiram

Abif whose fortitude should always be emulated by

every freemason.

![]()