|

The Legend Of The Winding Stairs

CHAPTER XXVI

the symbolism of freemasonry

albert gallatin mackey

Before proceeding to the examination of those more important mythical

legends which appropriately belong to the Master's degree, it will not, I

think, be unpleasing or uninstructive to consider the only one which is

attached to the Fellow Craft's degree—that, namely, which refers to the

allegorical ascent of the Winding Stairs to the Middle Chamber, and the

symbolic payment of the workmen's wages.

Although the legend of the Winding Stairs forms an important tradition

of Ancient Craft Masonry, the only allusion to it in Scripture is to be

found in a single verse in the sixth chapter of the First Book of Kings,

and is in these words: "The door for the middle chamber was in the right

side of the house; and they went up with winding stairs into the middle

chamber, and out of the middle into the third." Out of this slender

material has been constructed an allegory, which, if properly considered

in its symbolical relations, will be found to be of surpassing beauty. But

it is only as a symbol that we can regard this whole tradition; for the

historical facts and the architectural details alike forbid us for a

moment to suppose that the legend, as it is rehearsed in the second degree

of Masonry, is anything more than a magnificent philosophical myth.

Let us inquire into the true design of this legend, and learn the

lesson of symbolism which it is intended to teach.

In the investigation of the true meaning of every masonic symbol and

allegory, we must be governed by the single principle that the whole

design of Freemasonry as a speculative science is the investigation of

divine truth. To this great object everything is subsidiary. The Mason is,

from the moment of his initiation as an Entered Apprentice, to the time at

which he receives the full fruition of masonic light, an investigator—a

laborer in the quarry and the temple—whose reward is to be Truth. All the

ceremonies and traditions of the order tend to this ultimate design. Is

there light to be asked for? It is the intellectual light of wisdom and

truth. Is there a word to be sought? That word is the symbol of truth. Is

there a loss of something that had been promised? That loss is typical of

the failure of man, in the infirmity of his nature, to discover divine

truth. Is there a substitute to be appointed for that loss? It is an

allegory which teaches us that in this world man can only approximate to

the full conception of truth.

Hence there is in Speculative Masonry always a progress, symbolized by

its peculiar ceremonies of initiation. There is an advancement from a

lower to a higher state—from darkness to light—from death to life—from

error to truth. The candidate is always ascending; he is never stationary;

he never goes back, but each step he takes brings him to some new mental

illumination—to the knowledge of some more elevated doctrine. The teaching

of the Divine Master is, in respect to this continual progress, the

teaching of Masonry—"No man having put his hand to the plough, and looking

back, is fit for the kingdom of heaven." And similar to this is the

precept of Pythagoras: "When travelling, turn not back, for if you do the

Furies will accompany you."

Now, this principle of masonic symbolism is apparent in many places in

each of the degrees. In that of the Entered Apprentice we find it

developed in the theological ladder, which, resting on earth, leans its

top upon heaven, thus inculcating the idea of an ascent from a lower to a

higher sphere, as the object of masonic labor. In the Master's degree we

find it exhibited in its most religious form, in the restoration from

death to life—in the change from the obscurity of the grave to the holy of

holies of the Divine Presence. In all the degrees we find it presented in

the ceremony of circumambulation, in which there is a gradual inquisition,

and a passage from an inferior to a superior officer. And lastly, the same

symbolic idea is conveyed in the Fellow Craft's degree in the legend of

the Winding Stairs.

In an investigation of the symbolism of the Winding Stairs we shall be

directed to the true explanation by a reference to their origin, their

number, the objects which they recall, and their termination, but above

all by a consideration of the great design which an ascent upon them was

intended to accomplish.

The steps of this Winding Staircase commenced, we are informed, at the

porch of the temple; that is to say, at its very entrance. But nothing is

more undoubted in the science of masonic symbolism than that the temple

was the representative of the world purified by the Shekinah, or the

Divine Presence. The world of the profane is without the temple; the world

of the initiated is within its sacred walls. Hence to enter the temple, to

pass within the porch, to be made a Mason, and to be born into the world

of masonic light, are all synonymous and convertible terms. Here, then,

the symbolism of the Winding Stairs begins.

The Apprentice, having entered within the porch of the temple, has

begun his masonic life. But the first degree in Masonry, like the lesser

Mysteries of the ancient systems of initiation, is only a preparation and

purification for something higher. The Entered Apprentice is the child in

Masonry. The lessons which he receives are simply intended to cleanse the

heart and prepare the recipient for that mental illumination which is to

be given in the succeeding degrees.

As a Fellow Craft, he has advanced another step, and as the degree is

emblematic of youth, so it is here that the intellectual education of the

candidate begins. And therefore, here, at the very spot which separates

the Porch from the Sanctuary, where childhood ends and manhood begins, he

finds stretching out before him a winding stair which invites him, as it

were, to ascend, and which, as the symbol of discipline and instruction,

teaches him that here must commence his masonic labor—here he must enter

upon those glorious though difficult researches, the end of which is to be

the possession of divine truth. The Winding Stairs begin after the

candidate has passed within the Porch and between the pillars of Strength

and Establishment, as a significant symbol to teach him that as soon as he

has passed beyond the years of irrational childhood, and commenced his

entrance upon manly life, the laborious task of self-improvement is the

first duty that is placed before him. He cannot stand still, if he would

be worthy of his vocation; his destiny as an immortal being requires him

to ascend, step by step, until he has reached the summit, where the

treasures of knowledge await him.

The number of these steps in all the systems has been odd. Vitruvius

remarks—and the coincidence is at least curious—that the ancient temples

were always ascended by an odd number of steps; and he assigns as the

reason, that, commencing with the right foot at the bottom, the worshipper

would find the same foot foremost when he entered the temple, which was

considered as a fortunate omen. But the fact is, that the symbolism of

numbers was borrowed by the Masons from Pythagoras, in whose system of

philosophy it plays an important part, and in which odd numbers were

considered as more perfect than even ones. Hence, throughout the masonic

system we find a predominance of odd numbers; and while three, five,

seven, nine, fifteen, and twenty-seven, are all-important symbols, we

seldom find a reference to two, four, six, eight, or ten. The odd number

of the stairs was therefore intended to symbolize the idea of perfection,

to which it was the object of the aspirant to attain.

As to the particular number of the stairs, this has varied at different

periods. Tracing-boards of the last century have been found, in which only

five steps are delineated, and others in which they amount to

seven. The Prestonian lectures, used in England in the beginning of

this century, gave the whole number as thirty-eight, dividing them into

series of one, three, five, seven, nine, and eleven. The error of making

an even number, which was a violation of the Pythagorean principle of odd

numbers as the symbol of perfection, was corrected in the Hemming

lectures, adopted at the union of the two Grand Lodges of England, by

striking out the eleven, which was also objectionable as receiving a

sectarian explanation. In this country the number was still further

reduced to fifteen, divided into three series of three, five,

and seven. I shall adopt this American division in explaining the

symbolism, although, after all, the particular number of the steps, or the

peculiar method of their division into series, will not in any way affect

the general symbolism of the whole legend.

The candidate, then, in the second degree of Masonry, represents a man

starting forth on the journey of life, with the great task before him of

self-improvement. For the faithful performance of this task, a reward is

promised, which reward consists in the development of all his intellectual

faculties, the moral and spiritual elevation of his character, and the

acquisition of truth and knowledge. Now, the attainment of this moral and

intellectual condition supposes an elevation of character, an ascent from

a lower to a higher life, and a passage of toil and difficulty, through

rudimentary instruction, to the full fruition of wisdom. This is therefore

beautifully symbolized by the Winding Stairs; at whose foot the aspirant

stands ready to climb the toilsome steep, while at its top is placed "that

hieroglyphic bright which none but Craftsmen ever saw," as the emblem of

divine truth. And hence a distinguished writer has said that "these steps,

like all the masonic symbols, are illustrative of discipline and doctrine,

as well as of natural, mathematical, and metaphysical science, and open to

us an extensive range of moral and speculative inquiry."

The candidate, incited by the love of virtue and the desire of

knowledge, and withal eager for the reward of truth which is set before

him, begins at once the toilsome ascent. At each division he pauses to

gather instruction from the symbolism which these divisions present to his

attention.

At the first pause which he makes he is instructed in the peculiar

organization of the order of which he has become a disciple. But the

information here given, if taken in its naked, literal sense, is barren,

and unworthy of his labor. The rank of the officers who govern, and the

names of the degrees which constitute the institution, can give him no

knowledge which he has not before possessed. We must look therefore to the

symbolic meaning of these allusions for any value which may be attached to

this part of the ceremony.

The reference to the organization of the masonic institution is

intended to remind the aspirant of the union of men in society, and the

development of the social state out of the state of nature. He is thus

reminded, in the very outset of his journey, of the blessings which arise

from civilization, and of the fruits of virtue and knowledge which are

derived from that condition. Masonry itself is the result of civilization;

while, in grateful return, it has been one of the most important means of

extending that condition of mankind.

All the monuments of antiquity that the ravages of time have left,

combine to prove that man had no sooner emerged from the savage into the

social state, than he commenced the organization of religious mysteries,

and the separation, by a sort of divine instinct, of the sacred from the

profane. Then came the invention of architecture as a means of providing

convenient dwellings and necessary shelter from the inclemencies and

vicissitudes of the seasons, with all the mechanical arts connected with

it; and lastly, geometry, as a necessary science to enable the cultivators

of land to measure and designate the limits of their possessions. All

these are claimed as peculiar characteristics of Speculative Masonry,

which may be considered as the type of civilization, the former bearing

the same relation to the profane world as the latter does to the savage

state. Hence we at once see the fitness of the symbolism which commences

the aspirant's upward progress in the cultivation of knowledge and the

search after truth, by recalling to his mind the condition of civilization

and the social union of mankind as necessary preparations for the

attainment of these objects. In the allusions to the officers of a lodge,

and the degrees of Masonry as explanatory of the organization of our own

society, we clothe in our symbolic language the history of the

organization of society.

Advancing in his progress, the candidate is invited to contemplate

another series of instructions. The human senses, as the appropriate

channels through which we receive all our ideas of perception, and which,

therefore, constitute the most important sources of our knowledge, are

here referred to as a symbol of intellectual cultivation. Architecture, as

the most important of the arts which conduce to the comfort of mankind, is

also alluded to here, not simply because it is so closely connected with

the operative institution of Masonry, but also as the type of all the

other useful arts. In his second pause, in the ascent of the Winding

Stairs, the aspirant is therefore reminded of the necessity of cultivating

practical knowledge.

So far, then, the instructions he has received relate to his own

condition in society as a member of the great social compact, and to his

means of becoming, by a knowledge of the arts of practical life, a

necessary and useful member of that society.

But his motto will be, "Excelsior." Still must he go onward and

forward. The stair is still before him; its summit is not yet reached, and

still further treasures of wisdom are to be sought for, or the reward will

not be gained, nor the middle chamber, the abiding place of truth,

be reached.

In his third pause, he therefore arrives at that point in which the

whole circle of human science is to be explained. Symbols, we know, are in

themselves arbitrary and of conventional signification, and the complete

circle of human science might have been as well symbolized by any other

sign or series of doctrines as by the seven liberal arts and sciences. But

Masonry is an institution of the olden time; and this selection of the

liberal arts and sciences as a symbol of the completion of human learning

is one of the most pregnant evidences that we have of its antiquity.

In the seventh century, and for a long time afterwards, the circle of

instruction to which all the learning of the most eminent schools and most

distinguished philosophers was confined, was limited to what were then

called the liberal arts and sciences, and consisted of two branches, the

trivium and the quadrivium.154

The trivium included grammar, rhetoric, and logic; the

quadrivium comprehended arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy.

"These seven heads," says Enfield, "were supposed to include universal

knowledge. He who was master of these was thought to have no need of a

preceptor to explain any books or to solve any questions which lay within

the compass of human reason, the knowledge of the trivium having

furnished him with the key to all language, and that of the

quadrivium having opened to him the secret laws of nature."

155

At a period, says the same writer, when few were instructed in the

trivium, and very few studied the quadrivium, to be master

of both was sufficient to complete the character of a philosopher. The

propriety, therefore, of adopting the seven liberal arts and sciences as a

symbol of the completion of human learning is apparent. The candidate,

having reached this point, is now supposed to have accomplished the task

upon which he had entered—he has reached the last step, and is now ready

to receive the full fruition of human learning.

So far, then, we are able to comprehend the true symbolism of the

Winding Stairs. They represent the progress of an inquiring mind with the

toils and labors of intellectual cultivation and study, and the

preparatory acquisition of all human science, as a preliminary step to the

attainment of divine truth, which it must be remembered is always

symbolized in Masonry by the WORD.

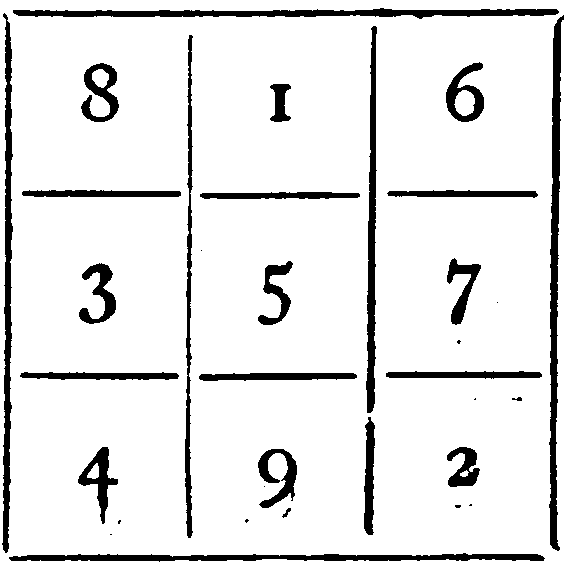

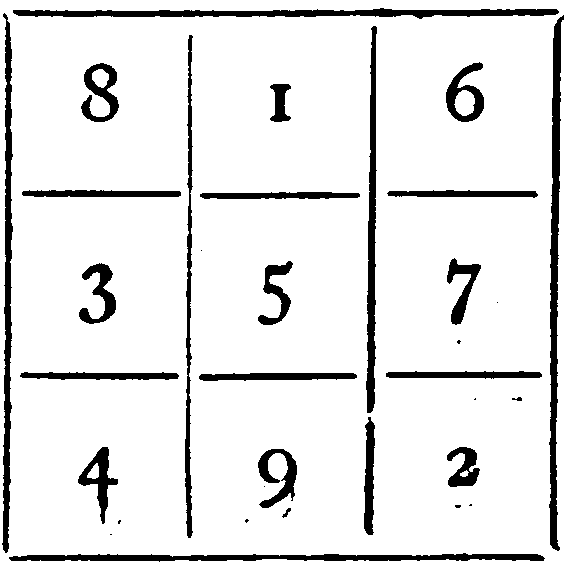

Here let me again allude to the symbolism of numbers, which is for the

first time presented to the consideration of the masonic student in the

legend of the Winding Stairs. The theory of numbers as the symbols of

certain qualities was originally borrowed by the Masons from the school of

Pythagoras. It will be impossible, however, to develop this doctrine, in

its entire extent, on the present occasion, for the numeral symbolism of

Masonry would itself constitute materials for an ample essay. It will be

sufficient to advert to the fact that the total number of the steps,

amounting in all to fifteen, in the American system, is a

significant symbol. For fifteen was a sacred number among the

Orientals, because the letters of the holy name JAH, יה, were, in their

numerical value, equivalent to fifteen; and hence a figure in which the

nine digits were so disposed as to make fifteen either way when added

together perpendicularly, horizontally, or diagonally, constituted one of

their most sacred talismans.156

The fifteen steps in the Winding Stairs are therefore symbolic of the name

of God.

But we are not yet done. It will be remembered that a reward was

promised for all this toilsome ascent of the Winding Stairs. Now, what are

the wages of a Speculative Mason? Not money, nor corn, nor wine, nor oil.

All these are but symbols. His wages are TRUTH, or that approximation to

it which will be most appropriate to the degree into which he has been

initiated. It is one of the most beautiful, but at the same time most

abstruse, doctrines of the science of masonic symbolism, that the Mason is

ever to be in search of truth, but is never to find it. This divine truth,

the object of all his labors, is symbolized by the WORD, for which we all

know he can only obtain a substitute; and this is intended to teach

the humiliating but necessary lesson that the knowledge of the nature of

God and of man's relation to him, which knowledge constitutes divine

truth, can never be acquired in this life. It is only when the portals of

the grave open to us, and give us an entrance into a more perfect life,

that this knowledge is to be attained. "Happy is the man," says the father

of lyric poetry, "who descends beneath the hollow earth, having beheld

these mysteries; he knows the end, he knows the origin of life."

The Middle Chamber is therefore symbolic of this life, where the symbol

only of the word can be given, where the truth is to be reached by

approximation only, and yet where we are to learn that that truth will

consist in a perfect knowledge of the G.A.O.T.U. This is the reward of the

inquiring Mason; in this consist the wages of a Fellow Craft; he is

directed to the truth, but must travel farther and ascend still higher to

attain it.

It is, then, as a symbol, and a symbol only, that we must study this

beautiful legend of the Winding Stairs. If we attempt to adopt it as an

historical fact, the absurdity of its details stares us in the face, and

wise men will wonder at our credulity. Its inventors had no desire thus to

impose upon our folly; but offering it to us as a great philosophical

myth, they did not for a moment suppose that we would pass over its

sublime moral teachings to accept the allegory as an historical narrative,

without meaning, and wholly irreconcilable with the records of Scripture,

and opposed by all the principles of probability. To suppose that eighty

thousand craftsmen were weekly paid in the narrow precincts of the temple

chambers, is simply to suppose an absurdity. But to believe that all this

pictorial representation of an ascent by a Winding Staircase to the place

where the wages of labor were to be received, was an allegory to teach us

the ascent of the mind from ignorance, through all the toils of study and

the difficulties of obtaining knowledge, receiving here a little and there

a little, adding something to the stock of our ideas at each step, until,

in the middle chamber of life,—in the full fruition of manhood,—the reward

is attained, and the purified and elevated intellect is invested with the

reward in the direction how to seek God and God's truth,—to believe this

is to believe and to know the true design of Speculative Masonry, the only

design which makes it worthy of a good or a wise man's study.

Its historical details are barren, but its symbols and allegories are

fertile with instruction. FOOTNOTES

154. The words themselves are purely classical, but the meanings here

given to them are of a mediaeval or corrupt Latinity. Among the old

Romans, a trivium meant a place where three ways met, and a

quadrivium where four, or what we now call a cross-road.

When we speak of the paths of learning, we readily discover the

origin of the signification given by the scholastic philosophers to these

terms.

155. Hist. of Philos. vol. ii. p. 337.

156. Such a talisman was the following figure:—

back to top |

![]()