|

The Ineffable Name

CHAPTER XXIV

the symbolism of freemasonry

albert gallatin mackey

Another important symbol is the Ineffable Name, with which the series

of ritualistic symbols will be concluded.

The Tetragrammaton,122

or Ineffable Word,—the Incommunicable Name,—is a

symbol—for rightly-considered it is nothing more than a symbol—that has

more than any other (except, perhaps, the symbols connected with

sun-worship), pervaded the rites of antiquity. I know, indeed, of no

system of ancient initiation in which it has not some prominent form and

place.

But as it was, perhaps, the earliest symbol which was corrupted by the

spurious Freemasonry of the pagans, in their secession from the primitive

system of the patriarchs and ancient priesthood, it will be most expedient

for the thorough discussion of the subject which is proposed in the

present paper, that we should begin the investigation with an inquiry into

the nature of the symbol among the Israelites.

That name of God, which we, at a venture, pronounce Jehovah,—although

whether this is, or is not, the true pronunciation can now never be

authoritatively settled,—was ever held by the Jews in the most profound

veneration. They derived its origin from the immediate inspiration of the

Almighty, who communicated it to Moses as his especial appellation, to be

used only by his chosen people; and this communication was made at the

Burning Bush, when he said to him, "Thus shalt thou say unto the children

of Israel: Jehovah, the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God

of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, hath sent me unto you: this [Jehovah] is

my name forever, and this is my memorial unto all generations."

123 And at a subsequent period he still more

emphatically declared this to be his peculiar name: "I am Jehovah;

and I appeared unto Abraham, unto Isaac, and unto Jacob, by the name of

El Shaddai; but by my name

Jehovah was I not known unto them."

124

It will be perceived that I have not here followed precisely the

somewhat unsatisfactory version of King James's Bible, which, by

translating or anglicizing one name, and not the other, leaves the whole

passage less intelligible and impressive than it should be. I have

retained the original Hebrew for both names. El Shaddai, "the Almighty

One," was the name by which he had been heretofore known to the preceding

patriarchs; in its meaning it was analogous to Elohim, who is described in

the first chapter of Genesis as creating the world. But his name of

Jehovah was now for the first time to be communicated to his people.

Ushered to their notice with all the solemnity and religious

consecration of these scenes and events, this name of God became invested

among the Israelites with the profoundest veneration and awe. To add to

this mysticism, the Cabalists, by the change of a single letter, read the

passage, "This is my name forever," or, as it is in the original, Zeh

shemi l'olam, זה שמי לעלם as if written Zeh shemi l'alam, זה

שמי לאלם that is to say, "This is my name to be concealed."

This interpretation, although founded on a blunder, and in all

probability an intentional one, soon became a precept, and has been

strictly obeyed to this day.125

The word Jehovah is never pronounced by a pious

Jew, who, whenever he meets with it in Scripture, substitutes for it the

word Adonai or Lord—a practice which has been followed by

the translators of the common English version of the Bible with almost

Jewish scrupulosity, the word "Jehovah" in the original being invariably

translated by the word "Lord."

126 The pronunciation of the word, being thus

abandoned, became ultimately lost, as, by the peculiar construction of the

Hebrew language, which is entirely without vowels, the letters, being all

consonants, can give no possible indication, to one who has not heard it

before, of the true pronunciation of any given word.

To make this subject plainer to the reader who is unacquainted with the

Hebrew, I will venture to furnish an explanation which will, perhaps, be

intelligible.

The Hebrew alphabet consists entirely of consonants, the vowel sounds

having always been inserted orally, and never marked in writing until the

"vowel points," as they are called, were invented by the Masorites, some

six centuries after the Christian era. As the vowel sounds were originally

supplied by the reader, while reading, from a knowledge which he had

previously received, by means of oral instruction, of the proper

pronunciation of the word, he was necessarily unable to pronounce any word

which had never before been uttered in his presence. As we know that

Dr. is to be pronounced Doctor, and Mr. Mister,

because we have always heard those peculiar combinations of letters thus

enunciated, and not because the letters themselves give any such sound; so

the Jew knew from instruction and constant practice, and not from the

power of the letters, how the consonants in the different words in daily

use were to be vocalized. But as the four letters which compose the word

Jehovah, as we now call it, were never pronounced in his presence,

but were made to represent another word, Adonai, which was

substituted for it, and as the combination of these four consonants would

give no more indication for any sort of enunciation than the combinations

Dr. or Mr. give in our language, the Jew, being ignorant of

what vocal sounds were to be supplied, was unable to pronounce the word,

so that its true pronunciation was in time lost to the masses of the

people.

There was one person, however, who, it is said, was in possession of

the proper sound of the letters and the true pronunciation of the word.

This was the high priest, who, receiving it from his predecessor,

preserved the recollection of the sound by pronouncing it three times,

once a year, on the day of the atonement, when he entered the holy of

holies of the tabernacle or the temple.

If the traditions of Masonry on this subject are correct, the kings,

after the establishment of the monarchy, must have participated in this

privilege; for Solomon is said to have been in possession of the word, and

to have communicated it to his two colleagues at the building of the

temple.

This is the word which, from the number of its letters, was called the

"tetragrammaton," or four-lettered name, and, from its sacred

inviolability, the "ineffable" or unutterable name.

The Cabalists and Talmudists have enveloped it in a host of mystical

superstitions, most of which are as absurd as they are incredible, but all

of them tending to show the great veneration that has always been paid to

it.127

Thus they say that it is possessed of unlimited powers,

and that he who pronounces it shakes heaven and earth, and inspires the

very angels with terror and astonishment.

The Rabbins called it "shem hamphorash," that is to say, "the name that

is declaratory," and they say that David found it engraved on a stone

while digging into the earth.

From the sacredness with which the name was venerated, it was seldom,

if ever, written in full, and, consequently, a great many symbols, or

hieroglyphics, were invented to express it. One of these was the letter י

or Yod, equivalent nearly to the English I, or J, or Y, which was

the initial of the word, and it was often inscribed within an equilateral

triangle, thus:

the triangle itself being a symbol of Deity.

This symbol of the name of God is peculiarly worthy of our attention,

since not only is the triangle to be found in many of the ancient

religions occupying the same position, but the whole symbol itself is

undoubtedly the origin of that hieroglyphic exhibited in the second degree

of Masonry, where, the explanation of the symbolism being the same, the

form of it, as far as it respects the letter, has only been anglicized by

modern innovators. In my own opinion, the letter G, which is used

in the Fellow Craft's degree, should never have been permitted to intrude

into Masonry; it presents an instance of absurd anachronism, which would

never have occurred if the original Hebrew symbol had been retained. But

being there now, without the possibility of removal, we have only to

remember that it is in fact but the symbol of a symbol.128

Widely spread, as I have already said, was this reverence for the name

of God; and, consequently, its symbolism, in some peculiar form, is to be

found in all the ancient rites.

Thus the Ineffable Name itself, of which we have been discoursing, is

said to have been preserved in its true pronunciation by the Essenes, who,

in their secret rites, communicated it to each other only in a whisper,

and in such form, that while its component parts were known, they were so

separated as to make the whole word a mystery.

Among the Egyptians, whose connection with the Hebrews was more

immediate than that of any other people, and where, consequently, there

was a greater similarity of rites, the same sacred name is said to have

been used as a password, for the purpose of gaining admission to their

Mysteries.

In the Brahminic Mysteries of Hindostan the ceremony of initiation was

terminated by intrusting the aspirant with the sacred, triliteral name,

which was AUM, the three letters of which were symbolic of the creative,

preservative, and destructive principles of the Supreme Deity, personified

in the three manifestations of Bramah, Siva, and Vishnu. This word was

forbidden to be pronounced aloud. It was to be the subject of silent

meditation to the pious Hindoo.

In the rites of Persia an ineffable name was also communicated to the

candidate after his initiation.129

Mithras, the principal divinity in these rites, who

took the place of the Hebrew Jehovah, and represented the sun, had this

peculiarity in his name—that the numeral value of the letters of which it

was composed amounted to precisely 365, the number of days which

constitute a revolution of the earth around the sun, or, as they then

supposed, of the sun around the earth.

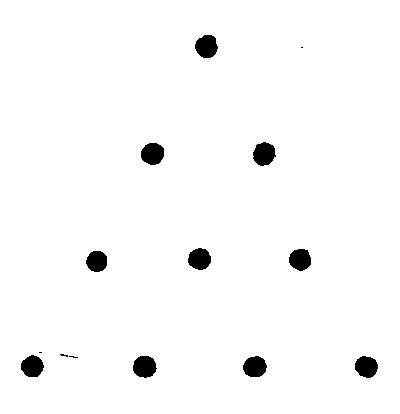

In the Mysteries introduced by Pythagoras into Greece we again find the

ineffable name of the Hebrews, obtained doubtless by the Samian Sage

during his visit to Babylon.130

The symbol adopted by him to express it was, however,

somewhat different, being ten points distributed in the form of a

triangle, each side containing four points, as in the annexed figure.

The apex of the triangle was consequently a single point then followed

below two others, then three; and lastly, the base consisted of four.

These points were, by the number in each rank, intended, according to the

Pythagorean system, to denote respectively the monad, or active

principle of nature; the duad, or passive principle; the

triad, or world emanating from their union; and the

quaterniad, or intellectual science; the whole number of points

amounting to ten, the symbol of perfection and consummation. This figure

was called by Pythagoras the tetractys—a word equivalent in

signification to the tetragrammaton; and it was deemed so sacred

that on it the oath of secrecy and fidelity was administered to the

aspirants in the Pythagorean rites.131

Among the Scandinavians, as among the Jewish Cabalists, the Supreme God

who was made known in their mysteries had twelve names, of which the

principal and most sacred one was Alfader, the Universal Father.

Among the Druids, the sacred name of God was Hu132—a

name which, although it is supposed, by Bryant, to have been intended by

them for Noah, will be recognized as one of the modifications of the

Hebrew tetragrammaton. It is, in fact, the masculine pronoun in Hebrew,

and may be considered as the symbolization of the male or generative

principle in nature—a sort of modification of the system of Phallic

worship.

This sacred name among the Druids reminds me of what is the latest, and

undoubtedly the most philosophical, speculation on the true meaning, as

well as pronunciation, of the ineffable tetragrammaton. It is from the

ingenious mind of the celebrated Lanci; and I have already, in another

work, given it to the public as I received it from his pupil, and my

friend, Mr. Gliddon, the distinguished archaeologist. But the results are

too curious to be omitted whenever the tetragrammaton is discussed.

Elsewhere I have very fully alluded to the prevailing sentiment among

the ancients, that the Supreme Deity was bisexual, or hermaphrodite,

including in the essence of his being the male and female principles, the

generative and prolific powers of nature. This was the universal doctrine

in all the ancient religions, and was very naturally developed in the

symbol of the phallus and cteis among the Greeks, and in the

corresponding one of the lingam and yoni among the

Orientalists; from which symbols the masonic point within a circle

is a legitimate derivation. They all taught that God, the Creator, was

both male and female.

Now, this theory is undoubtedly unobjectionable on the score of

orthodoxy, if we view it in the spiritual sense, in which its first

propounders must necessarily have intended it to be presented to the mind,

and not in the gross, sensual meaning in which it was subsequently

received. For, taking the word sex, not in its ordinary and

colloquial signification, as denoting the indication of a particular

physical organization, but in that purely philosophical one which alone

can be used in such a connection, and which simply signifies the mere

manifestation of a power, it is not to be denied that the Supreme Being

must possess in himself, and in himself alone, both a generative and a

prolific power. This idea, which was so extensively prevalent among all

the nations of antiquity,133

has also been traced in the tetragrammaton, or name of

Jehovah, with singular ingenuity, by Lanci; and, what is almost equally as

interesting, he has, by this discovery, been enabled to demonstrate what

was, in all probability, the true pronunciation of the word.

In giving the details of this philological discovery, I will endeavor

to make it as comprehensible as it can be made to those who are not

critically acquainted with the construction of the Hebrew language; those

who are will at once appreciate its peculiar character, and will excuse

the explanatory details, of course unnecessary to them.

The ineffable name, the tetragrammaton, the shem hamphorash,—for it is

known by all these appellations,—consists of four letters, yod, heh,

vau, and heh, forming the word יהוה. This word, of course, in

accordance with the genius of the Hebrew language, is read, as we would

say, backward, or from right to left, beginning with yod [י], and

ending with heh [ה].

Of these letters, the first, yod [י], is equivalent to the

English i pronounced as e in the word machine.

The second and fourth letter, heh [ה], is an aspirate, and has

here the sound of the English h.

And the third letter, vau [ו], has the sound of open

o.

Now, reading these four letters, י, or I, ה, or H, ו, or O, and ה, or

H, as the Hebrew requires, from right to left, we have the word יהוה, יהוה,

which is really as near to the pronunciation as we can well come,

notwithstanding it forms neither of the seven ways in which the word is

said to have been pronounced, at different times, by the patriarchs.134

But, thus pronounced, the word gives us no meaning, for there is no

such word in Hebrew as ihoh; and, as all the Hebrew names were

significative of something, it is but fair to conclude that this was not

the original pronunciation, and that we must look for another which will

give a meaning to the word. Now, Lanci proceeds to the discovery of this

true pronunciation, as follows:—

In the Cabala, a hidden meaning is often deduced from a word by

transposing or reversing its letters, and it was in this way that the

Cabalists concealed many of their mysteries.

Now, to reverse a word in English is to read its letters from right

to left, because our normal mode of reading is from left to right.

But in Hebrew the contrary rule takes place, for there the normal mode of

reading is from right to left; and therefore, to reverse the

reading of a word, is to read it from left to right.

Lanci applied this cabalistic mode to the tetragrammaton, when he found

that IH-OH, being read reversely, makes the word HO-HI.135

But in Hebrew, ho is the masculine pronoun, equivalent to the

English he; and hi is the feminine pronoun, equivalent to

she; and therefore the word HO-HI, literally translated, is

equivalent to the English compound HE-SHE; that is to say, the Ineffable

Name of God in Hebrew, being read cabalistically, includes within itself

the male and female principle, the generative and prolific energy of

creation; and here we have, again, the widely-spread symbolism of the

phallus and the cteis, the lingam and the yoni, or their equivalent, the

point within a circle, and another pregnant proof of the connection

between Freemasonry and the ancient Mysteries.

And here, perhaps, we may begin to find some meaning for the hitherto

incomprehensible passage in Genesis (i. 27): "So God created man in his

own image; in the image of God created he him; male and female

created he them." They could not have been "in the image" of IHOH, if they

had not been "male and female."

The Cabalists have exhausted their ingenuity and imagination in

speculations on this sacred name, and some of their fancies are really

sufficiently interesting to repay an investigation. Sufficient, however,

has been here said to account for the important position that it occupies

in the masonic system, and to enable us to appreciate the symbols by which

it has been represented.

The great reverence, or indeed the superstitious veneration,

entertained by the ancients for the name of the Supreme Being, led them to

express it rather in symbols or hieroglyphics than in any word at length.

We know, for instance, from the recent researches of the

archaeologists, that in all the documents of the ancient Egyptians,

written in the demotic or common character of the country, the names of

the gods were invariably denoted by symbols; and I have already alluded to

the different modes by which the Jews expressed the tetragrammaton. A

similar practice prevailed among the other nations of antiquity.

Freemasonry has adopted the same expedient, and the Grand Architect of the

Universe, whom it is the usage, even in ordinary writing, to designate by

the initials G.A.O.T.U., is accordingly presented to us in a variety of

symbols, three of which particularly require attention. These are the

letter G, the equilateral triangle, and the All-Seeing Eye.

Of the letter G I have already spoken. A letter of the English

alphabet can scarcely be considered an appropriate symbol of an

institution which dates its organization and refers its primitive history

to a period long anterior to the origin of that language. Such a symbol is

deficient in the two elements of antiquity and universality which should

characterize every masonic symbol. There can, therefore, be no doubt that,

in its present form, it is a corruption of the old Hebrew symbol, the

letter yod, by which the sacred name was often expressed. This

letter is the initial of the word Jehovah, or Ihoh, as I

have already stated, and is constantly to be met with in Hebrew writings

as the symbol or abbreviature of Jehovah, which word, it will be

remembered, is never written at length. But because G is, in like

manner, the initial of God, the equivalent of Jehovah, this

letter has been incorrectly, and, I cannot refrain from again saying, most

injudiciously, selected to supply, in modern lodges, the place of the

Hebrew symbol.

Having, then, the same meaning and force as the Hebrew yod, the

letter G must be considered, like its prototype, as the symbol of

the life-giving and life-sustaining power of God, as manifested in the

meaning of the word Jehovah, or Ihoh, the generative and prolific energy

of the Creator.

The All-Seeing Eye is another, and a still more important,

symbol of the same great Being. Both the Hebrews and the Egyptians appear

to have derived its use from that natural inclination of figurative minds

to select an organ as the symbol of the function which it is intended

peculiarly to discharge. Thus the foot was often adopted as the symbol of

swiftness, the arm of strength, and the hand of fidelity. On the same

principle, the open eye was selected as the symbol of watchfulness, and

the eye of God as the symbol of divine watchfulness and care of the

universe. The use of the symbol in this sense is repeatedly to be found in

the Hebrew writers. Thus the Psalmist says (Ps. xxxiv. 15), "The eyes of

the Lord are upon the righteous, and his ears are open to their cry,"

which explains a subsequent passage (Ps. cxxi. 4), in which it is said,

"Behold, he that keepeth Israel shall neither slumber nor sleep."

136

On the same principle, the Egyptians represented Osiris, their chief

deity, by the symbol of an open eye, and placed this hieroglyphic of him

in all their temples. His symbolic name, on the monuments, was represented

by the eye accompanying a throne, to which was sometimes added an

abbreviated figure of the god, and sometimes what has been called a

hatchet, but which, I consider, may as correctly be supposed to be a

representation of a square.

The All-Seeing Eye may, then, be considered as a symbol of God

manifested in his omnipresence—his guardian and preserving character—to

which Solomon alludes in the Book of Proverbs (xv. 3), when he says, "The

eyes of Jehovah are in every place, beholding (or as it might be more

faithfully translated, watching) the evil and the good." It is a symbol of

the Omnipresent Deity.

The triangle is another symbol which is entitled to our

consideration. There is, in fact, no other symbol which is more various in

its application or more generally diffused throughout the whole system of

both the Spurious and the Pure Freemasonry.

The equilateral triangle appears to have been adopted by nearly all the

nations of antiquity as a symbol of the Deity.

Among the Hebrews, it has already been stated that this figure, with a

yod in the centre, was used to represent the tetragrammaton, or

ineffable name of God.

The Egyptians considered the equilateral triangle as the most perfect

of figures, and a representative of the great principle of animated

existence, each of its sides referring to one of the three departments of

creation—the animal, the vegetable, and the mineral.

The symbol of universal nature among the Egyptians was the right-angled

triangle, of which the perpendicular side represented Osiris, or the male

principle; the base, Isis, or the female principle; and the hypothenuse,

their offspring, Horus, or the world emanating from the union of both

principles.

All this, of course, is nothing more nor less than the phallus and

cteis, or lingam and yoni, under a different form.

The symbol of the right-angled triangle was afterwards adopted by

Pythagoras when he visited the banks of the Nile; and the discovery which

he is said to have made in relation to the properties of this figure, but

which he really learned from the Egyptian priests, is commemorated in

Masonry by the introduction of the forty-seventh problem of Euclid's First

Book among the symbols of the third degree. Here the same mystical

application is supplied as in the Egyptian figure, namely, that the union

of the male and female, or active and passive principles of nature, has

produced the world. For the geometrical proposition being that the squares

of the perpendicular and base are equal to the square of the hypothenuse,

they may be said to produce it in the same way as Osiris and Isis are

equal to, or produce, the world.

Thus the perpendicular—Osiris, or the active, male principle—being

represented by a line whose measurement is 3; and the base—Isis, or the

passive, female principle—by a line whose measurement is 4; then their

union, or the addition of the squares of these numbers, will produce a

square whose root will be the hypothenuse, or a line whose measurement

must be 5. For the square of 3 is 9, and the square of 4 is 16, and the

square of 5 is 25; but 9 added to 16 is equal to 25; and thus, out of the

addition, or coming together, of the squares of the perpendicular and

base, arises the square of the hypothenuse, just as, out of the coming

together, in the Egyptian system, of the active and passive principles,

arises, or is generated, the world.

In the mediaeval history of the Christian church, the great ignorance

of the people, and their inclination to a sort of materialism, led them to

abandon the symbolic representations of the Deity, and to depict the

Father with the form and lineaments of an aged man, many of which

irreverent paintings, as far back as the twelfth century, are to be found

in the religious books and edifices of Europe.137

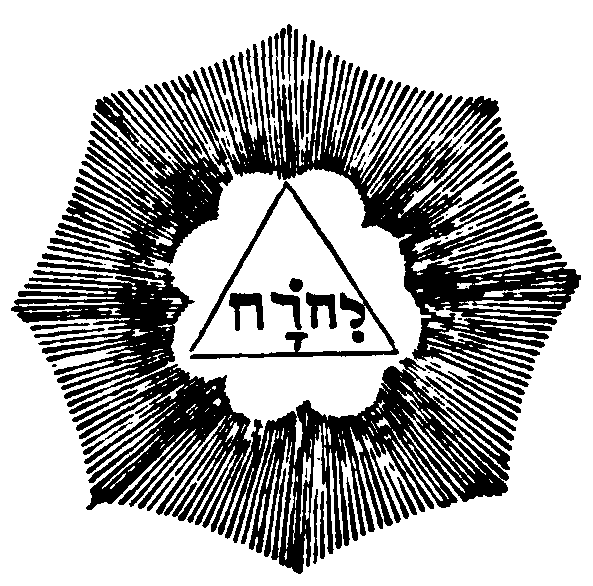

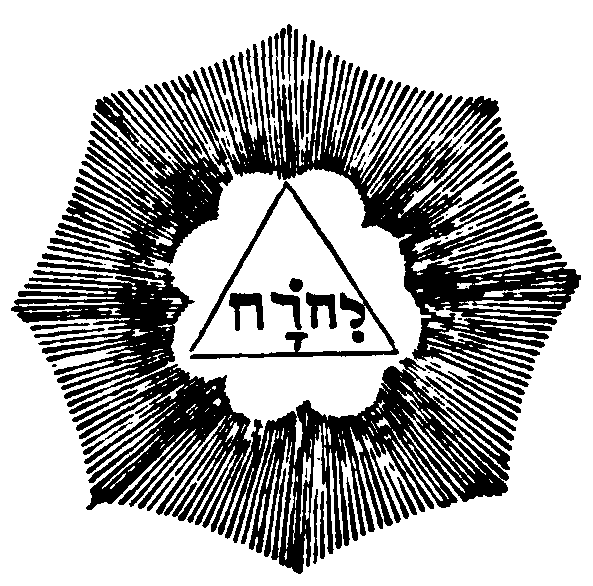

But, after the period of the renaissance, a better

spirit and a purer taste began to pervade the artists of the church, and

thenceforth the Supreme Being was represented only by his name—the

tetragrammaton—inscribed within an equilateral triangle, and placed within

a circle of rays. Didron, in his invaluable work on Christian Iconography,

gives one of these symbols, which was carved on wood in the seventeenth

century, of which I annex a copy.

But even in the earliest ages, when the Deity was painted or sculptured

as a personage, the nimbus, or glory, which surrounded the head of the

Father, was often made to assume a triangular form. Didron says on this

subject, "A nimbus, of a triangular form, is thus seen to be the exclusive

attribute of the Deity, and most frequently restricted to the Father

Eternal. The other persons of the trinity sometimes wear the triangle, but

only in representations of the trinity, and because the Father is with

them. Still, even then, beside the Father, who has a triangle, the Son and

the Holy Ghost are often drawn with a circular nimbus only."

138

The triangle has, in all ages and in all religions, been deemed a

symbol of Deity.

The Egyptians, the Greeks, and the other nations of antiquity,

considered this figure, with its three sides, as a symbol of the creative

energy displayed in the active and passive, or male and female,

principles, and their product, the world; the Christians referred it to

their dogma of the trinity as a manifestation of the Supreme God; and the

Jews and the primitive masons to the three periods of existence included

in the signification of the tetragrammaton—the past, the present, and the

future.

In the higher degrees of Masonry, the triangle is the most important of

all symbols, and most generally assumes the name of the Delta, in

allusion to the fourth letter of the Greek alphabet, which is of the same

form and bears that appellation.

The Delta, or mystical triangle, is generally surrounded by a circle of

rays, called a "glory." When this glory is distinct from the figure, and

surrounds it in the form of a circle (as in the example just given from

Didron), it is then an emblem of God's eternal glory. When, as is most

usual in the masonic symbol, the rays emanate from the centre of the

triangle, and, as it were, enshroud it in their brilliancy, it is symbolic

of the Divine Light. The perverted ideas of the pagans referred these rays

of light to their Sun-god and their Sabian worship.

But the true masonic idea of this glory is, that it symbolizes that

Eternal Light of Wisdom which surrounds the Supreme Architect as with a

sea of glory, and from him, as a common centre, emanates to the universe

of his creation, and to which the prophet Ezekiel alludes in his eloquent

description of Jehovah: "And I saw as the color of amber, as the

appearance of fire round about within it, from the appearance of his loins

even upward, and from his loins even downward, I saw, as it were, the

appearance of fire, and it had brightness round about." (Chap. 1, ver.

27.)

Dante has also beautifully described this circumfused light of Deity:—

"There is in heaven a light whose goodly shine

Makes the Creator

visible to all

Created, that in seeing him, alone

Have peace; and

in a circle spreads so far,

That the circumference were too loose a

zone

To girdle in the sun."

On a recapitulation, then, of the views that have been advanced in

relation to these three symbols of the Deity which are to be found in the

masonic system, we may say that each one expresses a different attribute.

The letter G is the symbol of the self-existent Jehovah.

The All-Seeing Eye is the symbol of the omnipresent God.

The triangle139

is the symbol of the Supreme Architect of the

Universe—the Creator; and when surrounded by rays of glory, it becomes a

symbol of the Architect and Bestower of Light.

And now, after all, is there not in this whole prevalence of the name

of God, in so many different symbols, throughout the masonic system,

something more than a mere evidence of the religious proclivities of the

institution? Is there not behind this a more profound symbolism, which

constitutes, in fact, the very essence of Freemasonry? "The names of God,"

said a learned theologian at the beginning of this century, "were intended

to communicate the knowledge of God himself. By these, men were enabled to

receive some scanty ideas of his essential majesty, goodness, and power,

and to know both whom we are to believe, and what we are to believe of

him."

And this train of thought is eminently applicable to the admission of

the name into the system of Masonry. With us, the name of God, however

expressed, is a symbol of DIVINE TRUTH, which it should be the incessant

labor of a Mason to seek. FOOTNOTES

122. From the Greek

τετρὰς, four, and γράμμα, letter, because it is composed of four Hebrew

letters. Brande thus defines it: "Among several ancient nations, the name

of the mystic number four, which was often symbolized to represent

the Deity, whose name was expressed by four letters." But this definition

is incorrect. The tetragrammaton is not the name of the number four,

but the word which expresses the name of God in four letters, and is

always applied to the Hebrew word only.

123. Exod. iii. 15.

In our common version of the Bible, the word "Lord" is substituted for

"Jehovah," whence the true import of the original is lost.

125. "The Jews have

many superstitious stories and opinions relative to this name, which,

because they were forbidden to mention in vain, they would not

mention at all. They substituted Adonai, &c., in its room,

whenever it occurred to them in reading or speaking, or else simply and

emphatically styled it השם the Name. Some of them attributed to a

certain repetition of this name the virtue of a charm, and others have had

the boldness to assert that our blessed Savior wrought all his miracles

(for they do not deny them to be such) by that mystical use of this

venerable name. See the Toldoth Jeschu, an infamously scurrilous

life of Jesus, written by a Jew not later than the thirteenth century. On

p. 7, edition of Wagenseilius, 1681, is a succinct detail of the manner in

which our Savior is said to have entered the temple and obtained

possession of the Holy Name. Leusden says that he had offered to give a

sum of money to a very poor Jew at Amsterdam, if he would only once

deliberately pronounce the name Jehovah; but he refused it by

saying that he did not dare."—Horae Solitariae, vol. i. p. 3.—"A

Brahmin will not pronounce the name of the Almighty, without drawing down

his sleeve and placing it on his mouth with fear and trembling."—MURRAY,

Truth of Revelation, p. 321.

126. The same

scrupulous avoidance of a strict translation has been pursued in other

versions. For Jehovah, the Septuagint substitutes "Κύριος," the Vulgate "Dominus,"

and the German "der Herr," all equivalent to "the Lord." The French

version uses the title "l'Eternel." But, with a better comprehension of

the value of the word, Lowth in his "Isaiah," the Swedenborgian version of

the Psalms, and some other recent versions, have restored the original

name.

127. In the

Talmudical treatise, Majan Hachochima, quoted by Stephelin

(Rabbinical Literature, i. p. 131), we are informed that rightly to

understand the shem hamphorash is a key to the unlocking of all mysteries.

"There," says the treatise, "shalt thou understand the words of men, the

words of cattle, the singing of birds, the language of beasts, the barking

of dogs, the language of devils, the language of ministering angels, the

language of date-trees, the motion of the sea, the unity of hearts, and

the murmuring of the tongue—nay, even the thoughts of the reins."

128. The gamma, Γ,

or Greek letter G, is said to have been sacred among the Pythagoreans as

the initial of Γεωμειρία or Geometry.

129. Vide Oliver,

Hist. Init. p. 68, note.

130. Jamblichus says

that Pythagoras passed over from Miletus to Sidon, thinking that he could

thence go more easily into Egypt, and that while there he caused himself

to be initiated into all the mysteries of Byblos and Tyre, and those which

were practised in many parts of Syria, not because he was under the

influence of any superstitious motives, but from the fear that if he were

not to avail himself of these opportunities, he might neglect to acquire

some knowledge in those rites which was worthy of observation. But as

these mysteries were originally received by the Phoenicians from Egypt, he

passed over into that country, where he remained twenty-two years,

occupying himself in the study of geometry, astronomy, and all the

initiations of the gods (πάσας θεῶν τελετάς), until he was carried a

captive into Babylon by the soldiers of Cambyses, and that twelve years

afterwards he returned to Samos at the age of sixty years.—Vit. Pythag,

cap. iii., iv.

131. "The sacred

words were intrusted to him, of which the Ineffable Tetractys, or name of

God, was the chief."—OLIVER, Hist. Init. p. 109.

132. "Hu, the

mighty, whose history as a patriarch is precisely that of Noah, was

promoted to the rank of the principal demon-god among the Britons; and, as

his chariot was composed of rays of the sun, it may be presumed that he

was worshipped in conjunction with that luminary, and to the same

superstition we may refer what is said of his light and swift

course."—DAVIES, Mythol. and Rites of the Brit. Druids, p. 110.

133. "All the male

gods (of the ancients) may be reduced to one, the generative energy; and

all the female to one, the prolific principle. In fact, they may all be

included in the one great Hermaphrodite, the ἀῥῤενοθηλυς who combines in

his nature all the elements of production, and who continues to support

the vast creation which originally proceeded from his will."—RUSSELL'S

Connection, i. p. 402.

134. It is a

tradition that it was pronounced in the following seven different ways by

the patriarchs, from Methuselah to David, viz.: Juha, Jeva, Jova, Jevo,

Jeveh, Johe, and Jehovah. In all these words the j is to

be pronounced as y, the a as ah, the e as a,

and the v as w.

135. The i is

to be pronounced as e, and the whole word as if spelled in English

ho-he.

136. In the

apocryphal "Book of the Conversation of God with Moses on Mount Sinai,"

translated by the Rev. W. Cureton from an Arabic MS. of the fifteenth

century, and published by the Philobiblon Society of London, the idea of

the eternal watchfulness of God is thus beautifully allegorized:—

"Then Moses said to the Lord, O Lord, dost thou sleep or not? The Lord

said unto Moses, I never sleep: but take a cup and fill it with water.

Then Moses took a cup and filled it with water, as the Lord commanded him.

Then the Lord cast into the heart of Moses the breath of slumber; so he

slept, and the cup fell from his hand, and the water which was therein was

spilled. Then Moses awoke from his sleep. Then said God to Moses, I

declare by my power, and by my glory, that if I were to withdraw my

providence from the heavens and the earth for no longer a space of time

than thou hast slept, they would at once fall to ruin and confusion, like

as the cup fell from thy hand."

137. I have in my

possession a rare copy of the Vulgate Bible, in black letter, printed at

Lyons, in 1522. The frontispiece is a coarsely executed wood cut, divided

into six compartments, and representing the six days of the creation. The

Father is, in each compartment, pictured as an aged man engaged in his

creative task.

138. Christian

Iconography, Millington's trans., vol. i. p. 59.

139. The triangle,

or delta, is the symbol of Deity for this reason. In geometry a single

line cannot represent a perfect figure; neither can two lines; three

lines, however, constitute the triangle or first perfect and demonstrable

figure. Hence this figure symbolizes the Eternal God, infinitely perfect

in his nature. But the triangle properly refers to God only in his quality

as an Eternal Being, its three sides representing the Past, the Present,

and the Future. Some Christian symbologists have made the three sides

represent the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost; but they evidently thereby

destroy the divine unity, making a trinity of Gods in the unity of a

Godhead. The Gnostic trinity of Manes consisted of one God and two

principles, one of good and the other of evil. The Indian trinity,

symbolized also by the triangle, consisted of Brahma, Siva, and Vishnu,

the Creator, Preserver, and Destroyer, represented by Earth, Water, and

Air. This symbolism of the Eternal God by the triangle is the reason why a

trinitarian scheme has been so prevalent in all religions—the three sides

naturally suggesting the three divisions of the Godhead. But in the Pagan

and Oriental religions this trinity was nothing else but a tritheism.

back to top |

![]()